Who paid Confederates in York? Who didn’t?

Second York County Courthouse

28 E. Market St., York

The situation

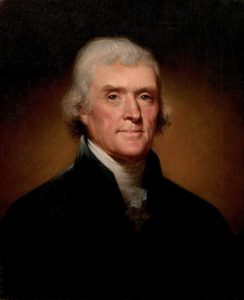

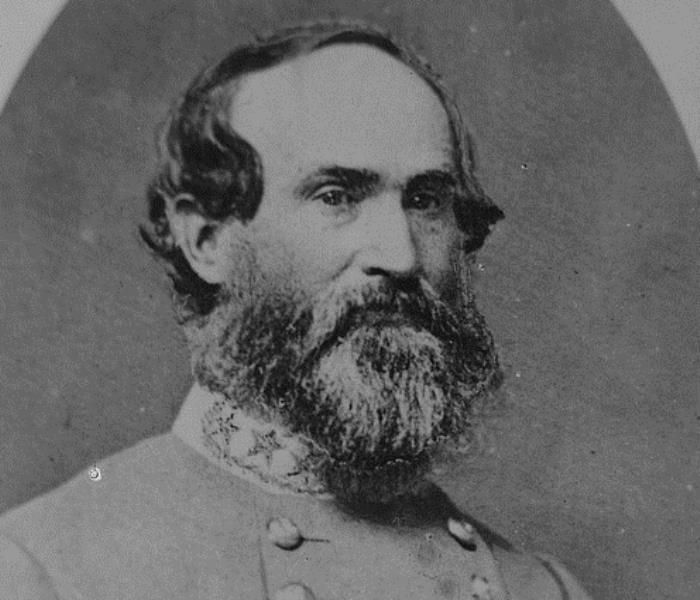

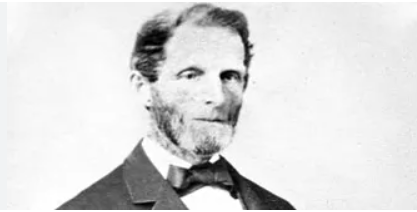

As part of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Pennsylvania campaign in the summer of 1863, Gen. Jubal Early’s division threatened to overrun largely undefended York County. Before the raiders touched county soil, a young York businessman without authorization met Confederate brigade commander John B. Gordon and cut a preliminary surrender deal – no resistance in exchange for safety of York property and people. The businessman, A.B. Farquhar, and a delegation took a second trip later that day, June 27, 1863, to ratify the surrender.

The Confederates entered York the next day, and occupied it for two days, persistently prying goods and money from residents. A brigade rode on to Wrightsville in an attempt to capture the Susquehanna River bridge, but Union forces torched the structure to stop the rebel advance. Lee recalled Gordon and the rest of Jubal Early’s 6,600-man division, which countermarched to Gettysburg – where it sustained heavy casualties in fighting on Cemetery Hill.

The surrender – particularly the way the town’s fathers sought out the Confederates to hand them the keys to the town – did not sit well with some local residents. And it remains a controversy today. It didn’t help with the enormous requisition levied by Early, headquartered at York County Courthouse, 28 E. Market St., the predecessor the York County Administrative Center. He demanded food: 165 barrels of flour or 28,000 pounds of baked bread; 3,500 pounds of sugar; 1,650 pounds of coffee; 300 gallons of molasses; 1,200 pounds of salt; 32,000 pounds of fresh beef or 21,000 pounds of bacon or pork. Clothing: 2,000 pairs of shoes or boots, 1,000 pairs of socks and 1,000 felt hats. The town came up with the food and supplies but only $28,600 of the $100,000 demanded.

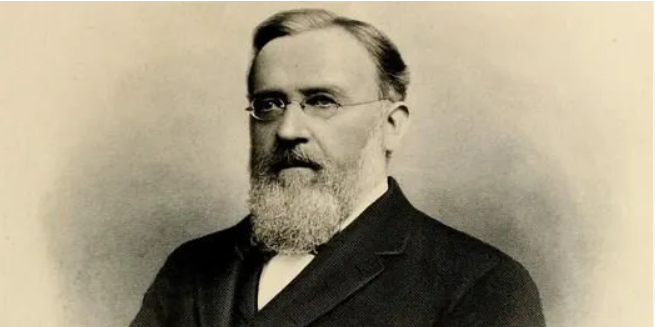

The leaders split up into teams to collect from residents. Interestingly, the two prime movers behind the seek-out-and-surrender decision – businessman Farquhar and Chief Burgess/newspaper owner David Small – did not appear to contribute funds to the requisition. For that story, please see: Who paid the Confederate requisition after York’s Civil War surrender? And who did not? And for more about the surrender’s downstream impact on York County’s story, see: York’s Civil War surrender of 1863: Why it matters (ydr.com).

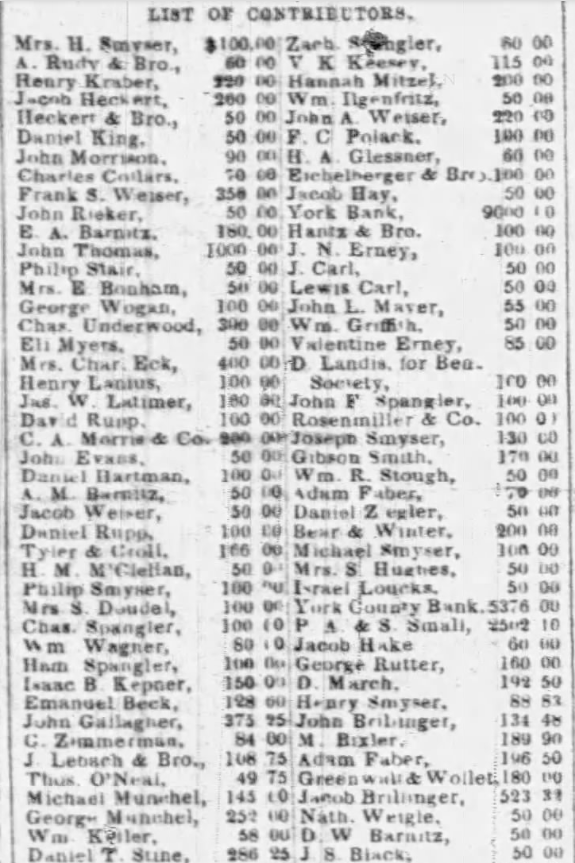

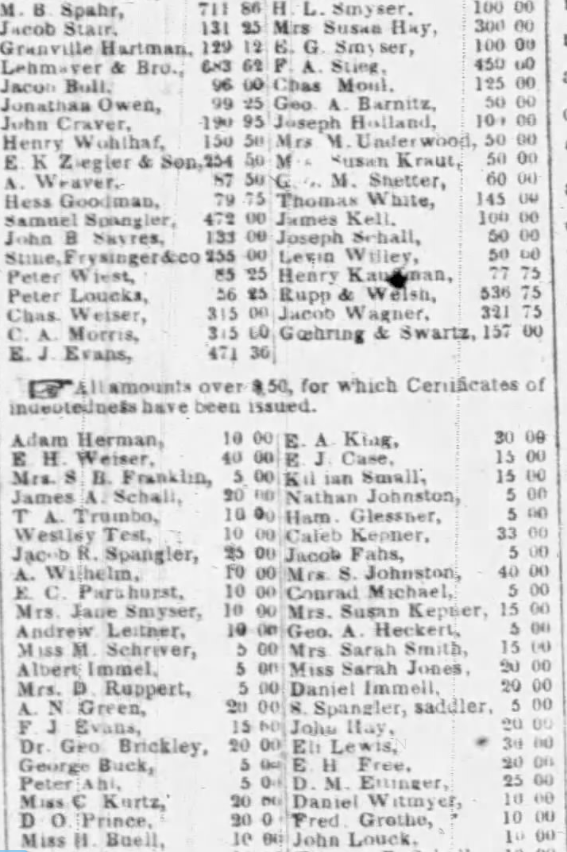

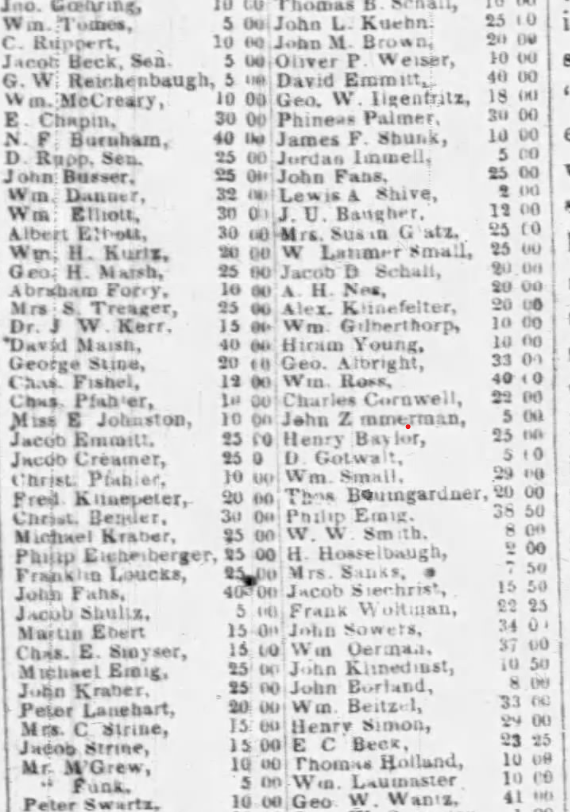

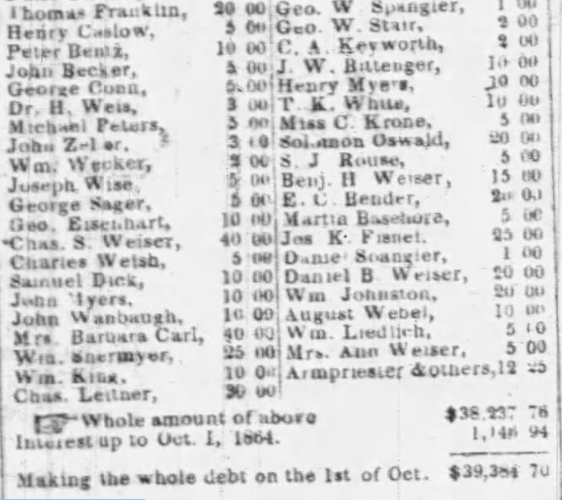

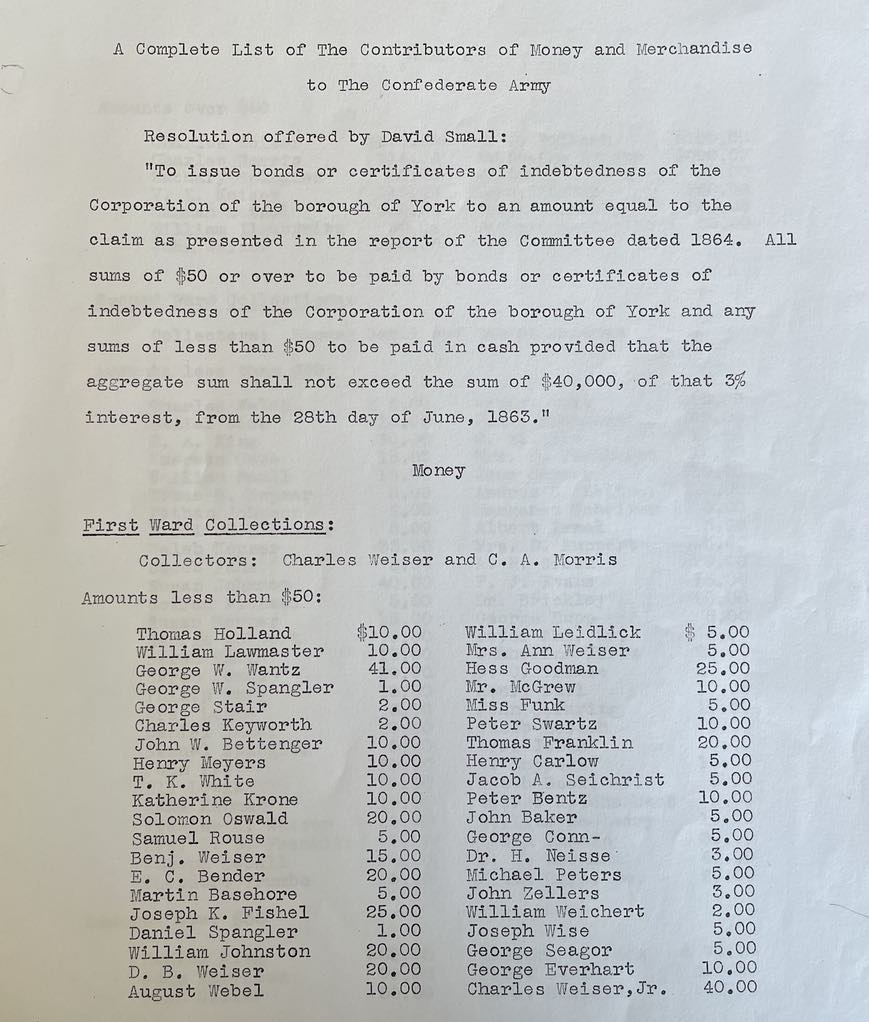

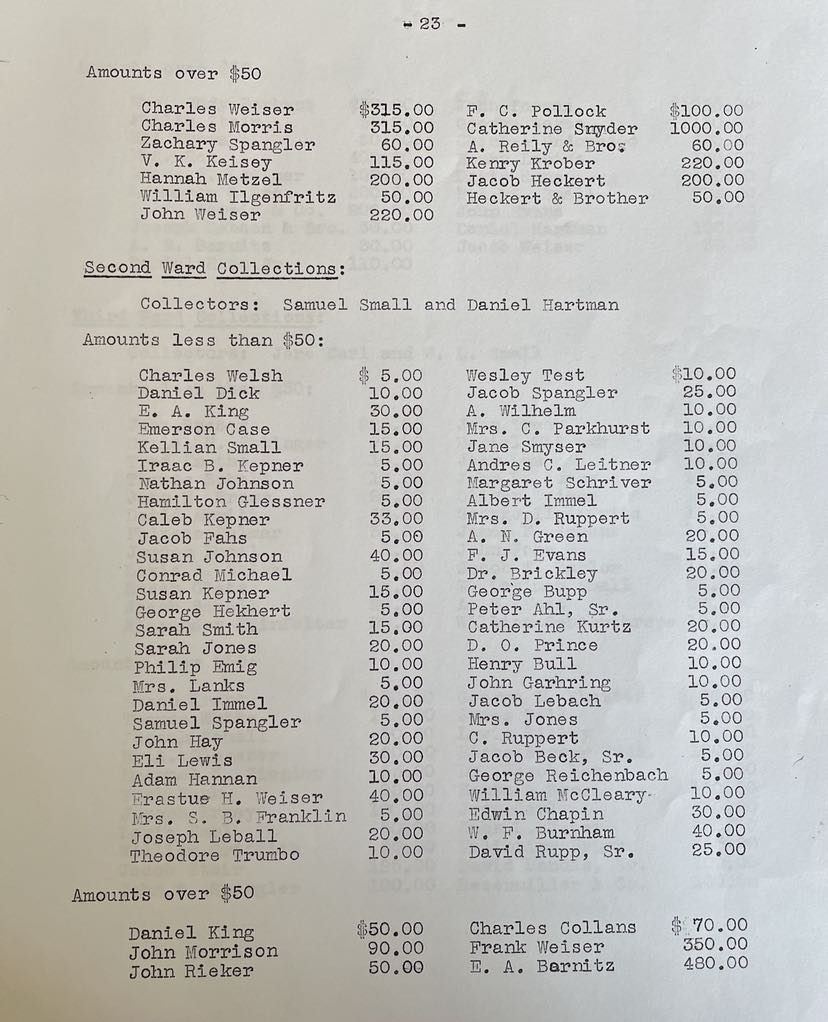

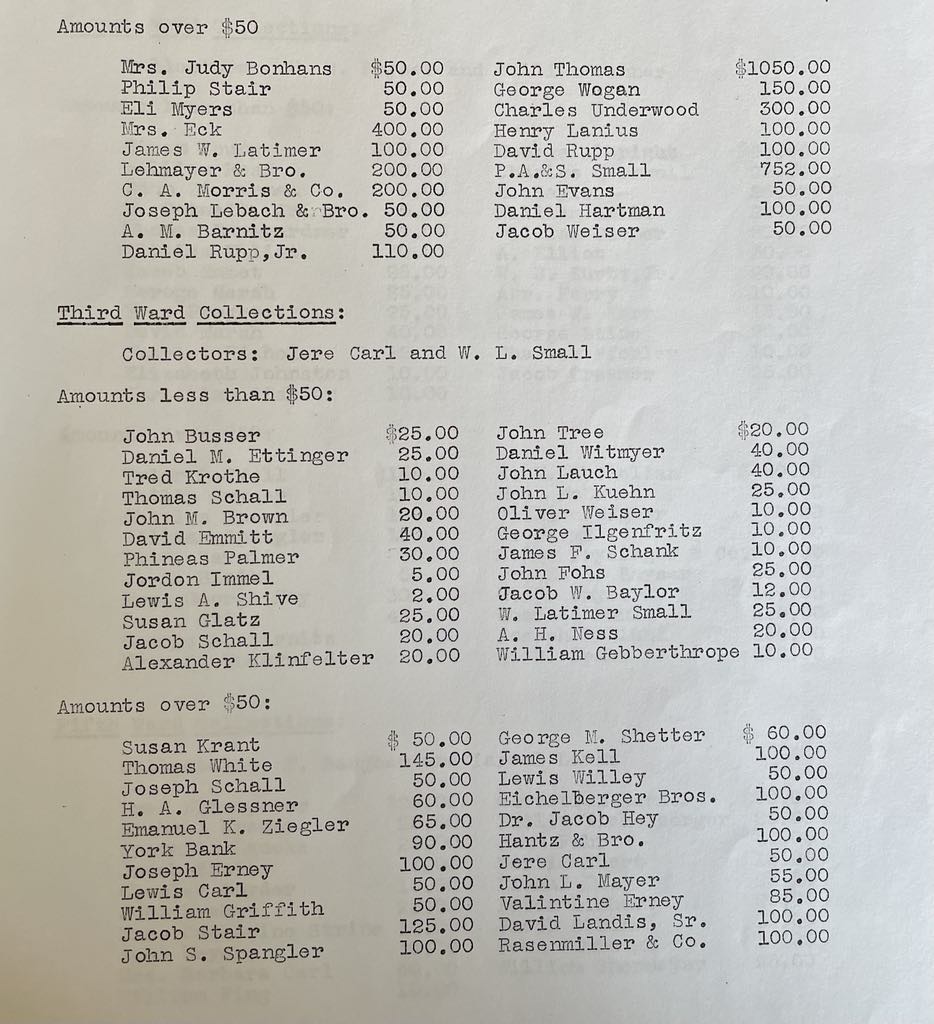

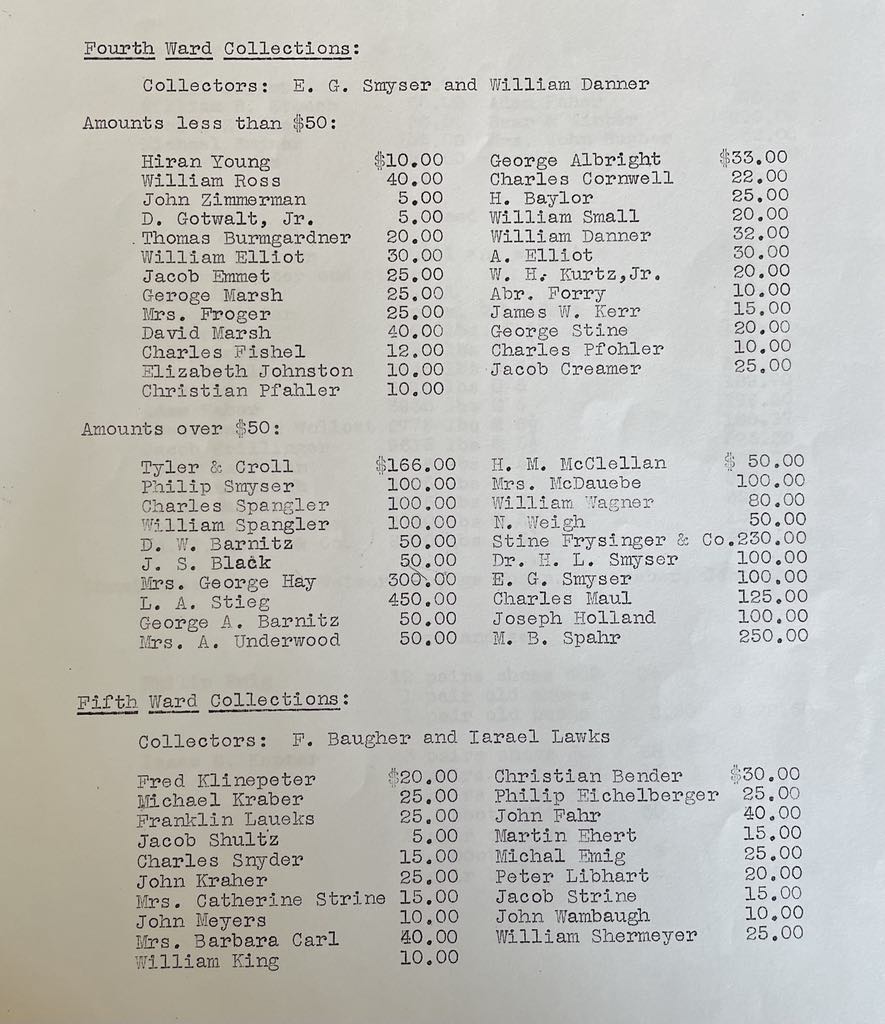

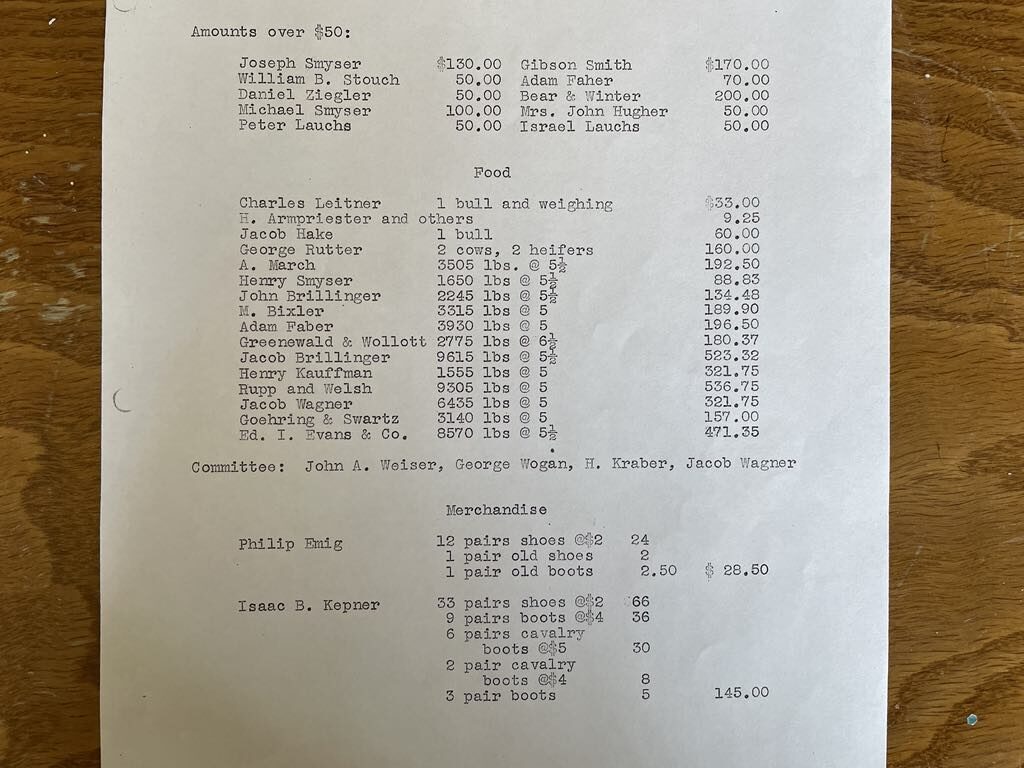

Two lists of who contributed to the requisition are known to exist. They appear below in “The Witness.”

Meanwhile, some observations:

P.A. and Samuel Small, the town’s leading businessmen, gave $752 according to one list and $2,502 per the other. Thomas White, one of the delegation to Farmers, provided $145. Col. George Hay, the sole military man in the Farmers group likely paid – a Mrs. George Hay is listed at $300. William Latimer Small of the Farmers delegation is listed at $25.

As for Farquhar case, it’s possible he did not live in York. But as he had made clear to all, he owned a factory in town. Perhaps Small, also publisher of the staunchly Democrat, anti-Lincoln York Gazette believed he had provided in-kind services, printing a handbill for Early and other such jobs.

It’s likely that some noteworthy people gave using the names of others. Historian Charles Glatfelter has noted that Catherine Miller paid the collectors $1,000. The next year, she married into the wealthy family of tobacconist — cigarmaker — William Danner, a requisition collector who also paid a small sum in his own name.

It’s also possible that some leaders simply refused to pay. Committee member Thomas Cochran’s name is missing from both lists, and the Gazette pointed out in publishing the list in 1865 that this owner of the competing York Republican was among the biggest critics of the surrender. James Latimer, the Republican who thought the borough authorities had acted “so sheepishly,” later reported that he “very foolishly” gave $100 to the solicitors, a decision he regretted.

Having said all this, it’s not a good look in a bad situation for Small and Farquhar to sit it out when others paid the Confederates for fear that the raiders roaming their streets would damage their town.

The witness

This list was published in the York Gazette in July 25, 1865:

+++

+++

+++

+++

This unsourced inventory appeared as part of a paper by Raymond E. Klein of Franklin & Marshall College, available in the York County History Center Archives:

Video: Scott Mingus talks about the surrender of York

Photos: The Civil War comes to York County, Pa. (ydr.com)

These quotes explain York during the Civil War

The question

When the Confederates occupied York after the surrender, they demanded $100,000, supplies and food from the townspeople. Some paid, some didn’t. What would you have done?

Related links and sources: Should York’s leaders have surrendered to Confederates? James McClure’s “East of Gettysburg.” Scott Mingus’ “Flames Beyond Gettysburg.” Top photo, York County History Center. Other photos, York Daily Record.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE