The Brownstone: Owner built community in York

The Brownstone: David E. Small offered his helping hand

153 E. Market St., York

The situation

It was Memorial Day 1893, and a column of Union veterans marched up York’s North George Street hill.

At Prospect Hill Cemetery, the veterans of Gen. John Sedgwick Post 37, Grand Army of the Republic, peeled off to enter the gates of Prospect Hill Cemetery. Members of this post of white Union veterans entered these grounds to honor fellow soldiers buried there.

The rest of the blue-clad column kept moving up the hill. These were members of the David E. Small Post 369, a York organization of Black veterans. Past the hill’s crest, they exited George Street to assemble in the town’s historically Black burial grounds, Lebanon Cemetery. There, they were met by friends and family, to honor what a newspaper called a “goodly” number of veterans buried there.

It was a day when Black and white veterans dressed in blue honored their fallen comrades together – and separately.

But one integrated part of the day could not be separated: The David E. Small Post was named after a white man.

The witness

David Etter Small was a partner in the Billmeyer and Small, maker of railroad cars. He was a Republican, a backer of Lincoln and only one arm away from serving in the Union Army.

He had lost his right arm before the Civil War in an industrial accident in one of his shops. He was determined to serve in the Union Army, but his disability prohibited him. “If I can bring down a partridge with a gun,” he once said, “I certainly can shoot well enough to go to the defence of my country.”

His enterprises gave him the means to build a substantial Italianate-style Brownstone at 153 E. Market St. in 1866. His railcar shops provided the network to aid enslaved people seeking freedom on the Underground Railroad.

“Mr. Small took a deep interest in the welfare of the colored people many a time giving them pecuniary aid and a helping hand on their way to freedom,” a community directory said after his death. “In remembrance of those kindnesses the colored soldiers of York have named their post David E. Small Post No. 369, G.A.R.”

The helping hand metaphor is on target. David Small used his only hand to aid blacks in many ways, including signing checks for their benefit. After his death in 1883, the largest bequest in his will went to the historically Black Lincoln University in Oxford, Pennsylvania. That kindness plus another gift to Lincoln came to $15,000 or equivalent to about $360,000 today.

In those days, it was rare for a post to be named after a civilian, blogger/historian Stephen H. Smith has observed. No. 369 was perhaps the only Black post in the U.S. to be named after a white civilian.

Today, David E. Small’s three-story brownstone has been renovated and joined to Martin Library forming one integrated structure. There, racially diverse York communities gather and connect, as they did in the early part of the Memorial Day Parade in 1893, through David E. Small’s extended hand to freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad and the kindness of GAR No. 369 members who honored him by taking on his name.

The questions

“Beware the binary,” I tell my students. It’s easy to put people, things, and ideas into two camps: good v. evil, black v. white, yes v. no. Why? Because it simplifies a complex topic.

In this story, we see the intricacies involving race, specifically how it isn’t as simple as “us v. them.” Not now, not ever. In what ways do binaries, or lumping things into one of two categories, limit our way of seeing?

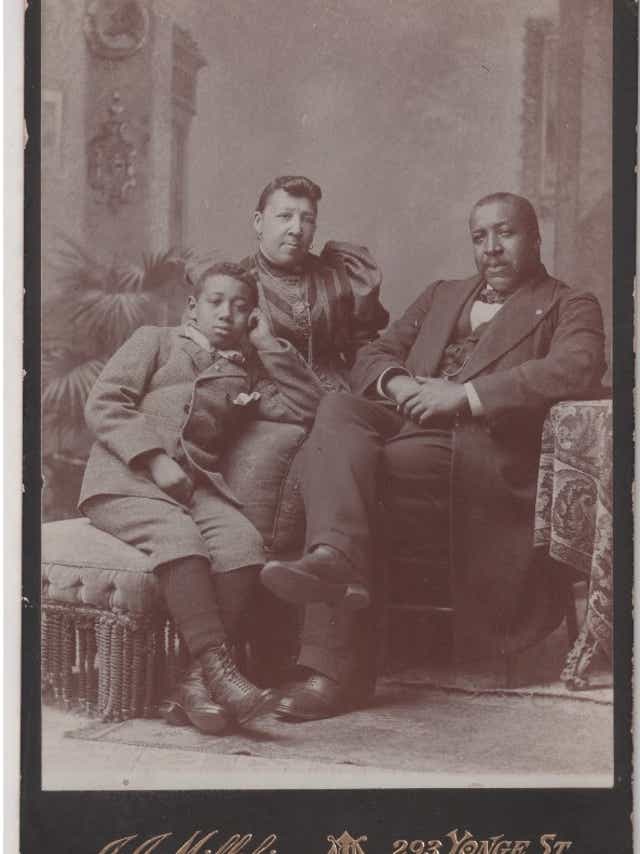

Related links and sources Stephen H. Smith’s “After Civil War, Veterans Organize in York County, in the 2015 Journal of York County Heritage. James McClure’s “East of Gettysburg.” Top photo and middle photo, YDR file. Bottom photo, Philip J. Merrill collection.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: Hometown History - Explore people, places and issues - Witnessing York