Hometown History: Jamie and Domi’s yoCo Backstory explores Penn Street Vision Plan

A walk to wonder:

Taking in Penn Street’s challenges and promise

York, PA

The situation

For their June 2023 Hometown History episode, Jamie Noerpel and Dominish Miller filmed at Penn Market in York, where they discussed the Penn Street Vision Plan. Their mile-long walk to wonder began at the south end of Penn Street’s Knowledge Park and the original village of Bottstown and ended at Farquhar Park.

While the east bank of the Codorus has seen investment such as the baseball stadium, Yorktowne Hotel, sculptures, and new sidewalks, the west side hasn’t received the same love. Some point out that things haven’t changed much… or at all. Particularly along Penn Street. Did the race riots of 1968-69 scare people away? Whatever the cause, parts of the Penn Street corridor and nearby Salem Square neighborhood have experienced poverty and violence.

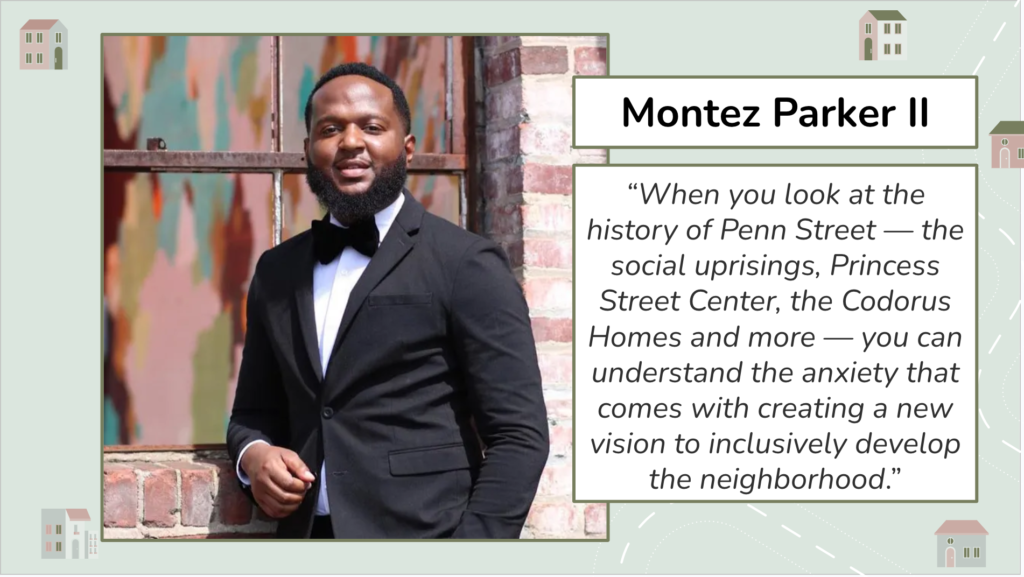

But today, there’s a call to action through empowering the community and investment. In April, Montez Parker II introduced the Penn Street Vision Plan. He, along with Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, interviewed residents of the neighborhood, community leaders, and local government agencies. The plan calls for the renovation of buildings, connection of green spaces, better housing, and increase of businesses.

This plan inspired Hometown History to do an episode on the Vision Plan through the lens of history. Their presentation consisted of three “takeaways”:

- Penn Street and its corridor is one of those city neighborhoods that hasn’t attracted investment. Parts of it are unchanged since it was a focal point of the York race riots in the 1968 and 1969. But there’s a plan now in place to spawn change.

- Difference markers, like Montez Parker II (who is from Penn Street corridor) may have left York, but many like him are coming back with a renewed vision. Despite a reputation to the contrary, millennials are becoming the next generation of leaders.

- If we could call the vision plan one word, it would be “coordinators.” The goal is not to bring in chain stores, but locally owned businesses and to help the people already living there with a hand up, not a hand out.

The walk

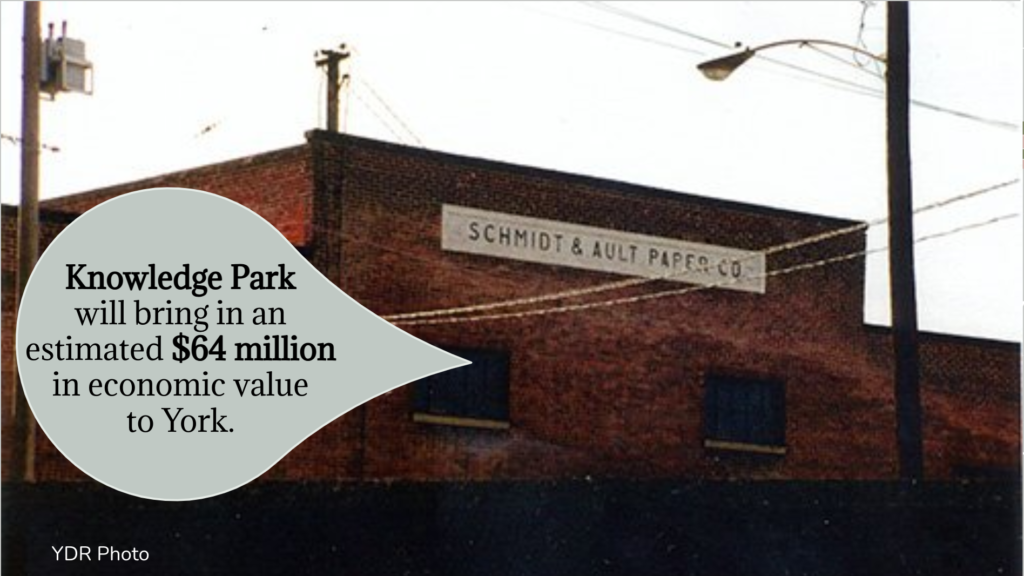

We’ll start at York College’s Knowledge Park. It’s called a “learning laboratory” that will allow for students and faculty to interact more with local businesses and organizations. It says the partnerships between higher education, industry, and the community will help everyone involved, especially students who need to compete for jobs in our ever-growing knowledge economy.

The Knowledge Park will bring in an estimated $64 million in economic value to York. Hundreds of new jobs, too, with over $27 million in income for locals. And these new employment opportunities don’t have to connect with YCP directly: There will be space-for-rent. It is being constructed on the 40-acre site of the former Schmidt and Ault paper mill.

Hermanus Bott was a farmer who immigrated to York from Germany. In 1753, he probably stood somewhere on the west bank, looking across the Codorus at the budding town of York. He envisioned a town that would compete with the then 12-year-old York. Surveyors laid out about 50 lots – 65-feet wide along what is today West Market and 460 feet long.

It became known as Bottstown, though York County’s earliest historians called it Buttstown. The next year, work started on a courthouse in York Town. Then they build market sheds beside that courthouse, strategically placed where major roads crossed in the center of town. Botts’ town could never catch up. The west bank did get an indoor market house — Penn Market today — but it took almost 100 years (just after the Civil War).

Penn Street marked its western border. Smysertown, Eberton (later West York) and The Avenues filled in agricultural land to the south and west and north. But by 1884, Hermanus Botts’ dream to compete with York had evaporated. Three hundred people lived there when the Borough of York absorbed the city in 1884.

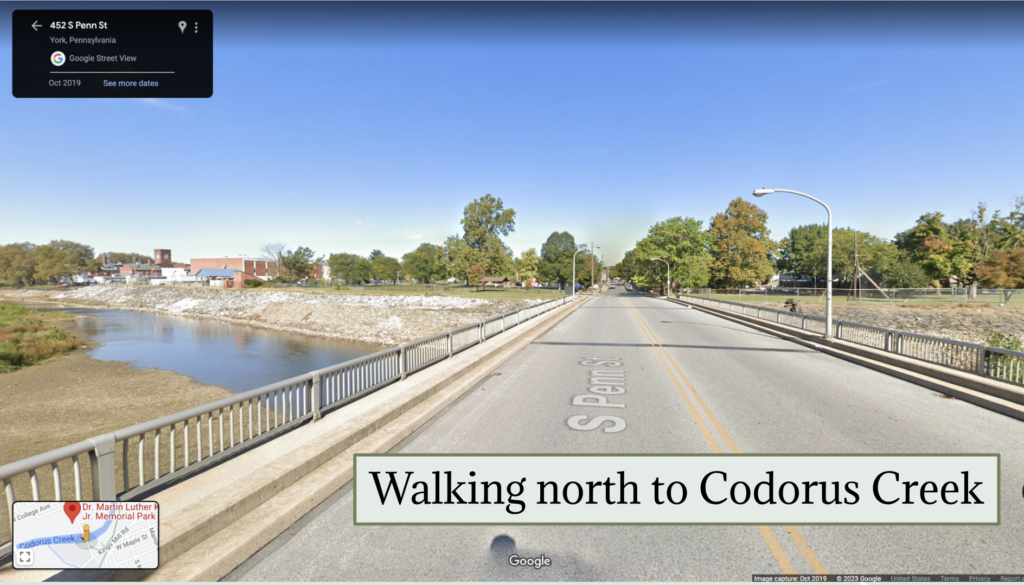

Walking north, we hit Codorus Creek. One-third of York County’s water drains into this creek. It not only sustains our ecosystems and waters our crops, but it also has been victimized by industrial and residential waste pollution for centuries. Its reputation of foul-smelling odors and filth earned it the nickname “Inky Stinky.” In recent decades, its water quality has improved and fishing is coming back! Unfortunately, dumping dates back to 1816. Reports of sewage and industrial waste darkening the water prompted people to look for alternatives. That’s when York Water began offering fresh water in wooden pipes and continued into the 20th century.

But the planned YCEA’s Codorus Beautification Initiative will change that. The plan will improve public access along both sides of the creek. There will be more recreational amenities such as thriving plants and habitats and flood control to keep the city safe. It also will be a great place for rail trail users to relax. On the other side of Knowledge Park, the popular walking/biking trail – the York County Heritage Rail Trail – runs south to the Maryland line and north to Rudy Park.

What is now MLK Park used to be the Codorus Street Neighborhood. After the Civil War, industrialization boomed. York County offered employment in factories such as Dentsply, whose now-vacant buildings are visible from MLK Park, and Yorkco, now Johnson Controls, visible from North Penn Street. After World War I, Black people from the South came north for these jobs in what is now known as the Great Migration.

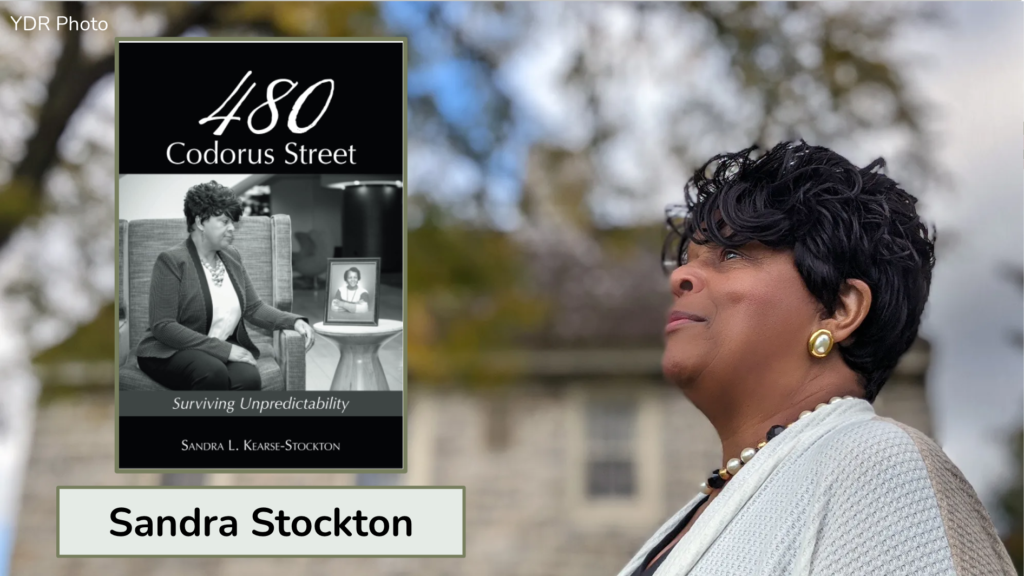

After finding a job, many settled down in the neighborhoods west of the Codorus. There were over 73 addresses from Penn Street to Green Street. They housed generations of Yorkers, including Sandra L Kearse-Stockton.

While families like Sandra’s escaped the horrors of southern racism, they still found themselves confronting discrimination during the Great Depression. Red lining created hurdles for people to get loans because the area has been identified as too poor to be worth the financial risk. These housing policies made it hard for people to own their own homes. It also discouraged investment, causing dilapidated housing. (Penn Street has a higher rate of ownership than the rest of York, interestingly).

In 1961, the Codorus Street neighborhood was torn down via eminent domain. The site became a green space in what today is known as MLK Park. The Vision plan calls for repairing the pavement and installing better walkways

Let’s quickly review what we learned so far: Originally, those early tenants of Bottstown were required to build a house at least 20-feet square with a brick/stone chimney and a lime/sand foundation – all of this in less than 2 years. They started to build on the fertile land of the Codorus Creek’s west bank in the 1700s.

The town hosted more Black migrants moving to the neighborhood into the 1920s. When the Great Depression hit, redlining and other discriminatory practices led to decline of this area.

Today, the Penn Street Vision plan made housing one of its main focus areas. The Penn Street Corridor contains 101 parcels – 78% are residential buildings. The other 22% are commercial, religious, or community spaces. Here are two themes of the vision plan:

- Access for all: As we’ve said, the Penn Street corridor actually has a higher level of homeownership compared to the rest of the city. The idea is to build on that, implementing plans like the state’s Whole Home Repairs Program that provides homeowners up to $50,000 to improve water and energy efficiencies and other habitation improvements.

- Expand development opportunities: Construct mixed-use buildings on vacant spaces or convert existing structures to mixed use.

We continue our walk north to Friendship Community Garden. There used to be a vacant lot when you hit West College. It was filled with weeds and litter. As Jim McClure wrote, “It served as a symbol, unfair in some cases, for that neighborhood. There is crime there, but many good people, too.”

About four years ago, YoKo and Robert Enomoto decided to change that. They created the Friendship Community Garden that cultivated neighborhood pride alongside their beautiful flowers and vegetables. This corner lot has even been called an “oasis of peace.” Years ago – in 1969 – this intersection was the location of a murder. In the York race revolts, assailants fired at an armored vehicle on the College Avenue Bridge carrying police officers, killing officer Henry Schaad.

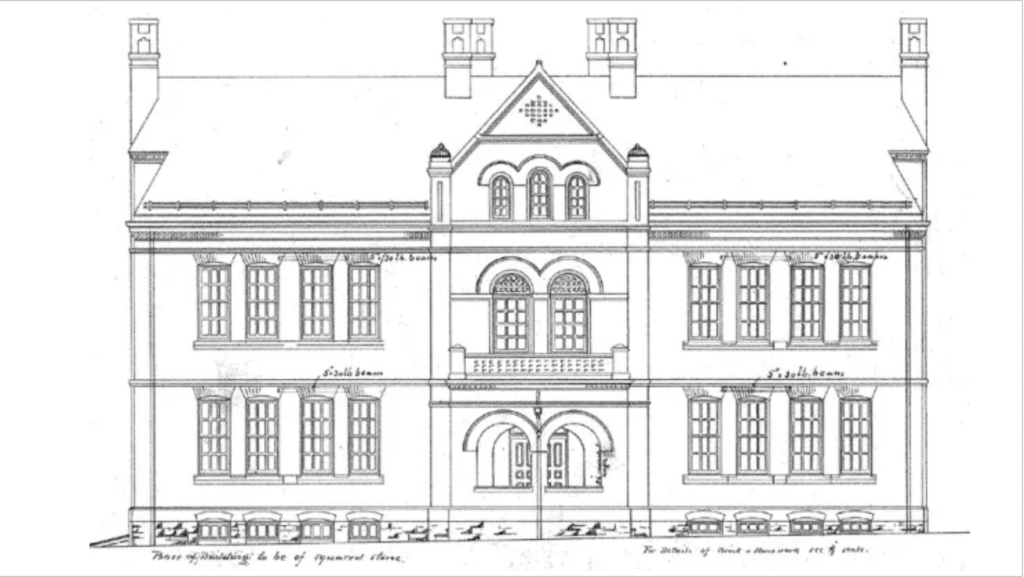

Walking right along to the Old Princess Street School. Built in 1889 by York’s Dempwolf design firm, the school was originally an all-white facility. It remained so until 1951 when it was integrated (Brown v. Board was in 1954) when Black students from the neighborhood started to attend.

For decades it served as a glue, connecting the community as a local hub with a long reputation for providing resources for families. It was closed after water damage, but has good bones. The vision plan calls for the renovation of the 7,500-square-foot building (city of York is the current owner) such as replacing windows and addressing mold.

We’re headed north to Penn Market. The original inhabitants of Bottstown had access to fresh foods brought in from farmers at a market in the center of town. Then, when the Industrial Revolution hit, York’s population grew in numbers, the residents spreading out. So, in 1866, The Farmers’ Market at Penn and Market was formed to service people west of the Codorus.

Our walk continues to the Penn Street Art Bridge. It was built in the 1990s to replace a bridge that motorists used to get over the old Western Maryland Railroad tracks. Today, it’s a public art space. Anyone is welcome to put up their art. There are “No rules,” their website reads, but there are “just two guidelines.” (To find out more, watch Hometown History’s SHORT where Jamie and Domi go deeper into the art bridge’s cultural significance.)

Jane Jacobs wrote a book called The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). She claimed that city planners of the 1950/60s ignored the rhythm and heart of cities. Instead of focusing on the people, they attempted to force “order.” A thriving city, she wrote, had active-use sidewalks. People who just drive through in their cars miss the point. They aren’t taking the time to see and experience.

When Jamie, Domi, and Jim McClure walked the street, they noticed some things. They saw cracked cement, tree roots, and upheaved slabs of concrete. All this made walkability difficult in places. The Penn Street Vision Plan noted the hazardous sidewalk conditions since pedestrians can’t always safely travel up and down the street. So, they added walkability of the streetscape to their plan.

As they walked, they passed people sitting outside with each other. Groups of two to three men or a woman getting her mail. People sitting on their stoops or looking out the windows of their businesses serve as public eyes on the streets. A sort of do-it-yourself surveillance.

We end our walk at Farquhar Park, which is one of the largest green spaces in York City. Founded in 1890s after A.B. Farquhar, a businessman who manufactured farming equipment, the park has a playground, tennis courts, walking paths, pavilions, & exercise stations. There used to be an amusement park near the park (current location of Ferguson Elementary School). It was called the White Rose Amusement Park – a fitting name – with a pool beside it. However, it wasn’t all fun and games. The city closed the pool due to polio epidemics, political issues, and racism, choosing to close rather than integrate.

The questions

Jamie and Domi ask you to remember these things: Parts of the Penn Street corridor have remained largely unchanged since the 1960s. Thankfully, locals like Montez Parker are bringing a renewed vision. The goal of the Penn Street Vision Plan is to serve as “coordinators,” so locals feel empowered to get involved.

What would be your takeaway? Or, if you could add a takeaway what would it be?

Related links and sources Penn Street Vision Plan, Jim McClure’s “It’s time – past time – for investment in York’s Penn Street corridor“; Montez Parker’s “In search of a new community normal.” This piece is based on the scripted followed in the Hometown History episode.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: Prime time ahead to take in York County history - Witnessing York