Amanda Berry Smith: ‘God’s image carved in ebony’

Amanda Berry Smith: She grew up in Underground Railroad house, then traveled the world

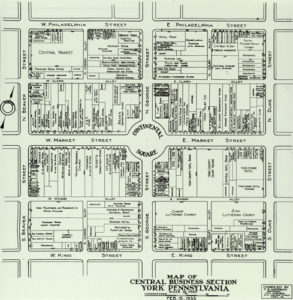

Baltimore-York Pike, south of Shrewsbury

Researchers Scott Mingus and Donna Peace have indicated that the site of the long-gone Samuel Berry Underground Railroad house (in blue) is the tenant house near John Lowe’s camp ground (red) on this 1860 map. The Blue Ball Tavern, standing today, is indicated by yellow. (See photo below).

The situation

Amanda Berry Smith, born enslaved but raised free in York County, would gain national stature as a well-traveled evangelist and a committed operator of a Chicago orphanage for Black children.

The things she witnessed as a youth in an Underground Railroad station and the model her parent offered would prepare her for such ventures.

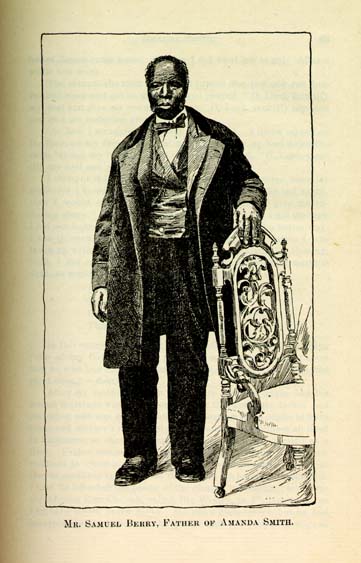

She wrote in her autobiography, for example, that her father, Samuel, would lead 15 to 20 men all day in the southern York County field. He would come home, sleep about two hours, then start at midnight with a freedom seeker on a 15-20 mile trek to a secure place. He would get home just before daylight. “Perhaps he could sleep an hour then go to work,” she wrote, “and so many times baffled suspicion.”

And her mother, Mariam, was a full partner in their station – a tenant house – on the John Lowe farm on the Baltimore-York Pike.

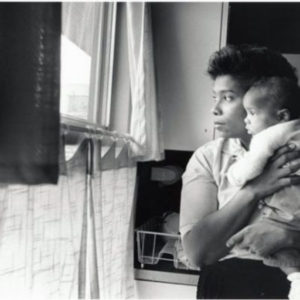

One day, slave catchers entered the house and began beating Samuel and “tramping” all over Amanda and her siblings. “We were screaming,” Amanda wrote, “There stood in the middle of the floor an old fashioned ten plate stove. There was no fire in it, of course, and as my poor frightened mother ran by it trying to defend father, she caught her wrapper in the door, just as a man cut at her with a spring dirk knife; it glanced on the door instead of on mother. I have thanked God many a time for that stove door.”

Yes, Amanda Berry Smith was equipped with a tenaciousness needed to hack her own path in the world.

York County hosts two Underground Railroad sites that are part of the National Park Service’s Network to Freedom inventory – the Goodridge House and Willis House, both in York. The Berry tenant house site, long gone, would be a third.

A historical marker in Shrewsbury briefly tells Amanda Berry Smith’s story. But until recently, the location of the Berry station was unknown, despite her careful documentation of the Berry’s Underground Railroad work. The work of two researchers – Scott Mingus and Donna Peace – have established its probable location.

Interstate 83 passes over this Underground Railroad site. You could say the site has transitioned from a stop over the Underground Railroad to a place under an overground expressway.

The witness

We know much about Amanda Berry Smith (1837-1915) because she left a personal account of her life.

She began Christian evangelistic work in 1869, after the death of her second husband and soon gained prominence in her preaching to both Black and white audiences. She is credited as the first Black woman to work as an international evangelist, preaching for 12 years in Great Britain, India and African countries.

She backed up her words with deeds, later operating the Chicago orphanage, writing a monthly newspaper “The Helper” that supported an institution for children, and publishing her autobiography in 1893. Indeed, she raised her own money for support of her various evangelistic missions.

Perhaps her tenderness for children reflects her family’s sacrificial work on the Underground Railroad south of Shrewsbury.

As she wrote after one visit by men seeking a man desperately seeking his freedom: “We children were sharp enough never to show any sign of alarm.”

In her autobiography, she reflected on the fact that “the Lord did provide,” in, among other things, permitting Samuel Berry to purchase his family’s freedom. He could then better aid others in gaining their freedom.

This accomplished woman, known as ‘God’s image carved in ebony,’ wrote:

“In some way or other

The Lord will provide;

It may not be my way,

It may not be thy way,

And yet in His own way,

The Lord will provide.”

The question

We know about Amanda Berry Smith because of her memoirs, titled An Autobiography. She not only learned how to read and write, but took the time to document her actions and beliefs. How many stories have been lost due to illiteracy? Or, worse yet, the lack of chronicling? What should we be documenting now so later generations will be able to learn from us like we are learning from Smith?

Related links and sources: Scott Mingus and James McClure’s “Civil War Stories from York County, Pennsylvania”; Documenting the American South, “Amanda Smith, 1837-1915.” Top photo, Scott Mingus. Berry portraits, from autobiography. Bottom photo, Scott Mingus.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: Unsung York County Civil War sites to visit - Witnessing York