Founders reach lows, highs in fight for Independence

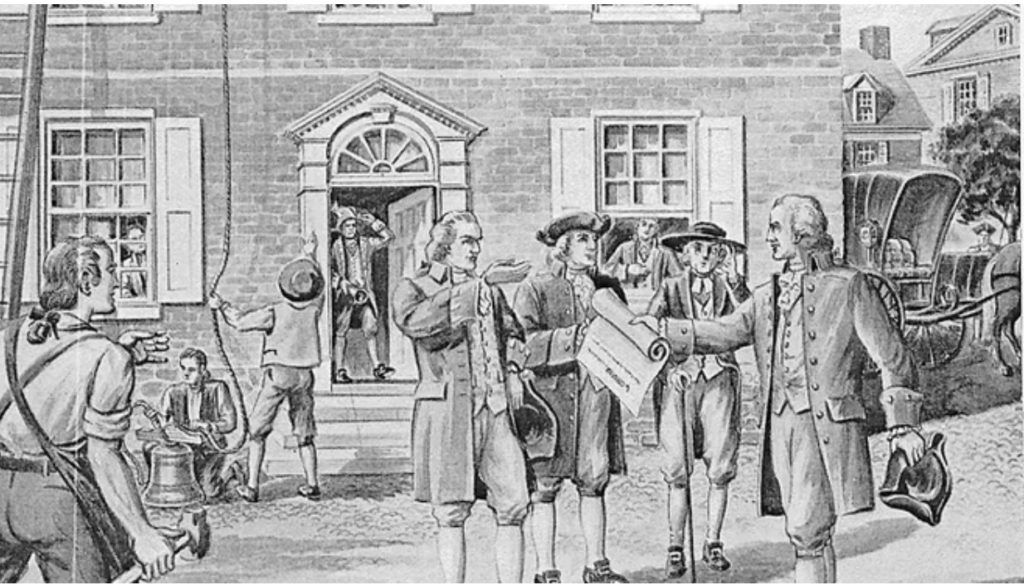

Centre Square Courthouse

Continental Square, York

The situation

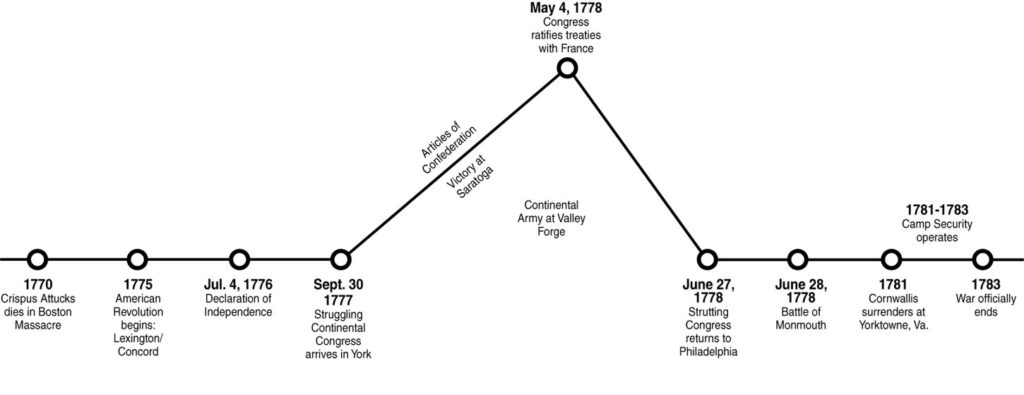

From America’s perspective, the Revolutionary War reached one new low point after another – on the battlefield and in the well of Continental Congress – until France came on as an ally.

Continental Congress in York, meeting in York for nine months in 1777-78, experienced the depths of despair, the rigors of everyday life in a frontier town and the joy of the alliance with France. With young men away fighting in the Continental Army, those left behind – women, children and the aged – did their part and more for the founders, military and civilians regularly arriving, staying and departing this national capital in time of war.

Here’s a summary of that story, the highs, lows and life in a revolution for freedom:

Before the curtain rises: Britain staggers under debt sustained in funding the nine-year French and Indian War, which ended in 1763. To cover this shortfall and other costs, Britain’s Parliament levies a series of taxes on its 13 American Colonies in the 1760s and early to mid-1770s.

Colonists bristle at these heavy levies, protests escalate and armed conflict bursts out in Concord and Lexington, Mass., in April 1775. The Revolutionary War thus began.

Meanwhile, many in York County mobilize with the same zeal for independence, forming patriotic committees and providing a company of soldiers to aid Continental Army forces in Boston within three months of “the shot heard ‘round the world” in Concord.

Through the American Revolution’s end, York County supports the military effort, although as in most wars, enthusiasm wanes and fewer recruits step forward as the fighting winds change.

On center stage: Americans train their nervous eyes on York Town when members of the Continental Congress, forced from comfortable seats in Philadelphia by the British, move to a frontier haven safe from the enemy army. They settle in York Town, on the edge of the frontier and across the wide Susquehanna River, on Sept. 30, 1777.

Sixty-four delegates, including 26 signers of the Declaration of Independence, join Congress in York Town. Some stay only days; a few for all 271 days.

York Town’s haven is not heaven for the men meeting in the town’s Centre Square courthouse. Wartime shortages and inflation tax their means. The citizens of York County, forced to support and house the delegates, their servants, messengers and attached military units, grow increasingly weary from the load.

This is the winter of Valley Forge, cloudy, even stormy, times for the American cause. But the sun pokes through with the arrival of the messenger in May 1778 declaring France’s support for the patriots. The adoption of the Articles of Confederation, America’s first constitution, five months earlier helped bring France aboard.

The British Army’s nine-month occupation of Philadelphia finally ends. The British leave Philadephia. The Continental Congress heads back east to fill the vacuum, leaving behind memories lasting in York Town – now called York – to this day.

The backdrop: York County offers spare fare in late September 1777. York Town, sprouting where the Monocacy Road crosses the Codorus Creek, serves as a staging area for people and wagons rolling deeper into America’s back country.

The 21-year-old York County Court House stands tall at the center of town, where roads going toward all key compass points meet. The brick structure represents justice for those living on the frontier. A market house perches to the west of the courthouse, a place for the agriculturally based community to barter and sell its surplus fruit, vegetables and meat.

York Town, just past its 35th birthday, is now a town of about 1,700 people living in log, wood, brick and stone residences hugging dusty streets in the summer and rutted mud bog in the winter. The German language commonly comes from the lips of townspeople. Congregants in three large churches in town hear sermons in the German tongue each Sunday.

The courthouse serves as the government center, the churches convey spiritual nourishment, and the plentiful taverns and inns along the streets provide for the social scene. Owners sought 18 licenses for public houses in 1765, three times the number of churches.

Authorities welcome the inns and taverns. These public gathering places give people an opportunity to say their piece, about the war.

The characters:

-In Congress, John and Abigail Adams: John Adams, one author says, was “vain, pedantic, intolerant, self-conscience and suffered because he knew he was.” The correspondence of this devoted Massachusetts husband and his equally engaged wife, Abigail, provides a window to view life in Congress and the 18th-century America. The self-educated Abigail writes with wits and poignancy on wide-ranging topics in her letters to John and others. John Hancock, Samuel Adams, Robert Morris and Richard Henry Lee were among other statesmen in York Town.

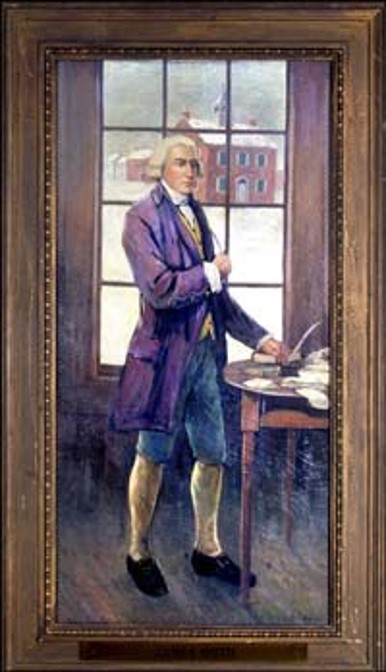

-In York Town, James and Eleanor Smith: James Smith, of Congress’ elder statesmen, plays hometown host to Congress in York Town. As York County’s leading patriot, this lawyer and raconteur is a fitting host, although he played a bit part in Congress’ deliberations. When tending to duties elsewhere, his patriotism and wit come through in his letters to Eleanor, his wife of more than 15 years.

The women of York played a key role, too. With scores of men away fighting the British, the women of York ran the farms and businesses and households and hosted the delegates, servants, military and other non-elected officials of the new American government. The visitors caustically complained about scarcity of food and high prices. The women and aged in York County encountered the same struggles.

Residents also endured Camp Security, a British POW camp in today’s Springettsbury Township, from 1781 to 1783. Some prisoners among the approximately 2,000 detained at the camp could come into York, causing friction among the townspeople.

-The soldiers, Marquis de Lafayette: This 20-year-old French nobleman comes to America to volunteer his services without pay or a command. His intelligence and enterprise quickly gain him friends and rank.

His trip to York to settle issues over his command of a planned invasion of Canada allows him to publicly back his then beleaguered friend and mentor George Washington, the Continental Army’s commander in chief, hunkered down in Valley Forge.

The action: The Conway Cabal, a loose-knit plot against Washington, was hitting empty when Congress was in York Town. Congress proclaimed a Day of Thanksgiving and Praise after the Saratoga victory. The Board of War, the defense department, was organized in York under Gen. Horatio Gates’ directorship.

But what type of work was done on the biggest deal – the Articles of Confederation – the framework of government under which the new nation would operate? Three issues needed to be resolved in York Town.

Congress resolved the mode of voting – one vote per state rather than by proportion of population. And then how should taxes be calculated – based on population or the value of land and improvements? Delegates decided the assessment for each state would be based on property values. When it came to population, delegates got hung up about how to count enslaved people.

The third issue – ownership of land stretching to the Mississippi – was not resolved. Congress adopted the Articles anyway, and sent the document to states for ratification.

That western land issue delayed the ratification process until 1781, when Maryland finally came on board. But the Articles were used to govern the nation from the framework’s adoption in York until the U.S. Constitution went into effect in 1789.

Here’s the thing: France wasn’t going to come aboard as an ally until America scores a constitution. How would France agree on a treaty if there wasn’t something to bind the 13 states into a nation? The Articles of Confederation was that constitution, and Congress ratified Treaties with France in early May 1778.

A complex plot: The irony of American statesmen fighting for independence from Britain when some owned enslaved people played in York Town.

Henry Laurens, president of Congress for most of its York Town stay, actively directed the affairs of his plantations, advising a friend not to sell one enslaved person, Doctor Cuffee, near his other plantations. As for another enslaved person, Laurens wrote: “… (L)et Zuma follow him immediately to Sale, if he once more elopes or comits any capital fault.”

In York, North Carolina delegate Cornelius Hartnett’s bondservant ran away, and the delegate offered a $20 reward if the enslaved Sawney was returned within 20 miles and $30 beyond that.

“I expect to set off the middle of April, & I fear, without a Servant to attend me,” he wrote, “as not one is to be had here as yet on any Terms.”

One hero among many: When Philip Livingston was preparing to leave his family in New York state to return to join the Continental Congress in 1778, he had a bad feeling about the trip to York.

“He was not in good shape,” a descendant said years later. “He said his farewells to his family because he didn’t think he’d make it back.”

Philip Livingston died in York, was remembered with a state funeral and today is one of two signers of the Declaration of Independence buried in York County. James Smith is the other.

The meaning of it all: In recent years, since the 225th anniversary of the Articles in 2002, York County has not focused on these nine months that York was in the middle of America’s quest for independence.

We’ve moved on to the Civil War and related issues – the Underground Railroad and slavery, for example – after years of silence on this era. That conversation is badly needed.

Community conversation is expected to click up with the 275th anniversary of the founding of York County in 2024, and the 250th of the Declaration of Independence in 2026, the Articles of Confederation in 2027 and the Treaties with France in 2028.

In the end, this story of the American Revolution in 1777-78 has an arc that bends toward victory versus the British. America’s founders came to York in the fall struggling without victory in the field or an agreement that 13 states could work as a nation. They left the next summer strutting with a constitution in their saddlebags and knowing French war ships would be in Atlantic waters when they returned to Philadelphia.

More: Drama plays out in York as America fought for its life (ydr.com)

The witness

It was Christmastime 1777, and Henry Laurens felt alone in York.

Forlorn. Depressed. Seemingly forgotten.

The wealthy South Carolinian and wealthy widower was in a rented room. In bed, aching from gout.

Not all of his family was down South. His son, John, was but 60 miles away. But he was needed in Valley Forge.

He was aide to George Washington, the great general himself cut off from loved ones for much of that Revolutionary War winter. That war would later claim John’s life – and that broke his father’s spirit.

Here Henry Laurens was in York, with the Continental Congress in the dark, early stages of an American Revolution that was looking bleak and offered no exit strategy. This Christmas, Congress possibly reached its lowest point America’s war for independence.

But Henry Laurens wasn’t just with Congress. He was president of Congress. And not many delegates had hung around that Christmas for him to lead.

At times that winter, maybe 10 delegates served as America’s governing body in that great war with Britain. Laurens would be one of three delegates who stayed in York for the entire nine months that Congress was in session.

Laurens’ gout confined him to bed, or to crutches, or to be carried back and forth between his quarters and the courthouse. Every day, he faced countless hours of work.

“Perhaps two, it may be three, hours after dark I may be permitted to hobble on my Crutches over Ice & frozen snow or to be carried to such a homely home as I have,” he wrote to a friend, “where I must set in Bed for one or two or three hours longer at the writing Table, pass the remainder of a tedious night in pain & some anxiety.”

He was tempted to turn in his delegate’s badge but reconsidered.

“I will not quit my post,” he wrote, “although I have some grounds to fear that I may perish on it.”

Even when his time as delegate was up a couple of years later, he shipped out to Europe as a diplomat to Holland. The British captured his ship and threw their prize prisoner in the Tower of London.

There, he stayed. Alone. That broke his health.

Henry Laurens was no saint. Sometimes, his letters from York to overseers in South Carolina showed concern about separating his troublesome slaves from each other lest their collusion lead to an uprising. In one of those ironies of history, he did such business at the same time that he was working for America’s independence from Britain.

But on the main, he lived and worked, often alone in York Town, for a great cause. Today, some see mainly the nation’s founders failures. Laurens melancholy at Christmas gives an idea of their sacrifice.

More: Henry Laurens in York, Pa.,: ‘I will not quit my post … .’ (ydr.com)

The questions

Henry Laurens is the “witness” we chose for this story. However, we could have selected a number of other individuals who played an important role in the Revolutionary War in York Town. If this was your article, who would you have chosen?

Related links and sources: James McClure’s “Nine Months in York Town, American Revolutionaries Labor on Pennsylvania’s frontier. Top photo, York County History Center. Colonial Mother, James Smith portraits, York County History Center. Other photos, York Daily Record

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE