Codorus Creek’s liquid Gold rush

The situation

Thomas Yingling, president of the Codorus Valley Area Historical Society, wrote this guest column for Witnessing York. It shows that even in well-watered York County, the quantity and quality of water can – and is – at risk a century ago and farther back. A York County water company siphoned water from a branch of the Codorus Creek in 1910, threatening the livelihoods of three millers. The millers went to court. And they won. This piece was originally published in the Codorus Valley Area Historical Society Newsletter March/April 2022.

Do you remember watching the old westerns on TV and in the movies? When rancher A would withhold water from rancher B, for some reason, a shootout or war would begin. The water was essential for the steer and horses to drink. Such events did happen but not just in the Wild West. They happened right here in southwestern York County along the West Branch of the Codorus Creek in the early 1900s. But there was not a war or shootout, rather a lawsuit.

On August 9, 1910, a lawsuit was filed against The Hanover and McSherrystown Water Company (H&MWC), by three mill owners along the west branch of the Codorus Creek in Heidelberg Township: William G. Kraft of Kraft’s Mill, Samuel F. Dubs of Dubs Mill and Alvin L. Menges of A. L. Menges & Bro. Mill (all in Heidelberg Township). The lawsuit involved the claim that H&MWC deprived the mill owners of water to run their mills. From the H&MWC pump station at Black Rock Road and Menges Mills, there were four mills. Three of the four, filed a lawsuit.

First, some background information:

Codorus Creek – The West Branch of the Codorus begins in West Manheim Township near the MD/PA line, east of Rt. 94. Two smaller creeks come together at Black Rock Road at what is now the western part of Lake Marburg to form the main branch. The two branches are currently named Furnace Creek (runs parallel to Pumping Station Rd.) and the West Branch Codorus Creek (runs parallel to Blackrock & Frogtown Rds.) However, that was not always the case. The current smaller West Branch was called Furnace Creek and the other branch, which runs along Pumping Station Rd., was called Slonaker Creek. This name changes to the current names, occurred sometime after 1915.

The main branch continues in a northeast direction (now though the middle of Lake Marburg) where it comes to where Kraft’s Mill was, at Kraft’s Mill and Hoff Roads. It takes an abrupt turn and winds northeast through Porters Sideling and on to Menges Mills at the northeast corner of Heidelberg Township. There is another branch of the West Branch that is also called the West Branch Codorus. This branch starts in Manheim Township, near Hokes. It travels northeast then north through Glenville, Brodbecks, Sinsheim and intersects with the main branch in front of the Lake Marburg dam near Kraft’s Mill.

The Hanover and McSherrystown Water Company (H&MWC) – In the early years of the Hanover area public water systems, companies were being formed, sold and bought in what seems like a short period of time. Several companies preceded the H&MWC, starting with the Hanover Water Company, 1872. Almost 20 years later, in 1893, the McSherrystown Water Company was created. Demand for more water grew in and around Hanover in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Population and industrial growth, as well as a greater need for fire protection, created this demand. This drove the need for more sources of water, and with it, the need for greater private investment. This dynamics is why smaller companies changed ownership so frequently. By 1895, the “Consumer’s Water Company of Hanover” was formed and had purchased both Hanover and the McSherrystown water companies. In 1905, Consumer’s Water of Hanover was sold to the newly created H&MWC, which soon became a subsidiary of the North American Water Works Corp. of New York City.

The main source of water had originally come from a collection of springs in the Pigeon Hills. That same year they began to build another pump station in the area where Black Rock Road, crosses Furnace and Slonaker creeks. These two water sources form the headwaters of the West Branch of the Codorus Creek. The old mill (Ruby’s Mill) was converted to a pump house for water. It also included a steam pump. The water from Furnace creek powered the pumps that pumped water from Slonaker creek. By 1905, larger pipes were installed, and even more water was being pumped out of the creek. As demand grew, by 1905, the south branch of the Conewago began to be used as a water source.

Kraft’s Mill (Bucher) (Leib) (Mummert): This was the first mill in this stretch of the West Branch and located about 4.5 miles from the juncture of Furnace and Slonaker creeks. The mill was said to have begun in 1796. It was a large mill of stone construction and utilized a ½ mile race. The first person to build this mill is yet uncertain. However, records suggest Michael Bucher, Sr. (1762 to 1831) & Christian Bucher (1779 to 1862) built it. They were uncle and nephew. Tax records indicate that it functioned as a Plaster, Grist and Saw mill. The mill was next sold in 1823 to Henry Leib (1793 to 1848) (never married). In 1848, the mill was inherited by Henry’s Father John, until he died in 1853, at which point the mill was sold to Jonas Mummert. By now it was no longer used as a plaster mill, just a grist and sawmill. In 1852, the Hanover Branch Railroad was constructed and ran right past the mill. Jonas Mummert (1825 to 1874), a previous resident of Paradise Township, purchased and operated the mill until 1865, when he sold it and moved his family to Illinois.

In 1863, when the Confederates came into York County and through nearby Jefferson, taking supplies all along the way, mills would have been an attractive target to acquire food. This may have led to Jonas selling his mill soon after. Jesse Kraft (1828 to 1910), from nearby Jefferson, purchased the mill in 1865 and modernized it by 1872, replacing the wooden water wheel with two S. Morgan Smith turbines (made in York) and adding other new equipment. Jesse retired from the milling business by 1892, selling it to his son William G. Kraft (1864 to 1941). William and a little later his son Ira (1889 to 1973) operated the mill until 1941. Upon William’s death, the foundation of the water wheel gave way and forced the mill to close for good. Around 1900, the S. Morgan Smith turbines were replaced, with a 5 foot wide by 12 foot diameter steel water wheel, made by the Fitz Water Wheel Co. of Hanover. More on this soon.

Dub’s Mill (Mumma) (J. Reynolds) (Hoffman) – The next mill, upstream, that was part of the lawsuit in 1910, was Dub’s Mill. It was 1-3/4 miles from Kraft’s Mill, just off Thoman and Hayrick Road along the creek, just northeast of Porter’s Sideling. Not a lot is known about this mill. The earliest owner known is John Mumma. The mill shows up on an 1816 & 1821 York County map as owned by a Hoffman. An 1860 map shows a B. Noel operated it as a sawmill. By 1876, a J. Reynolds also operated it as a sawmill. Samuel F. Dubs (1860 to 1949) was the owner of record as of the 1910 lawsuit. Samuel sold the land to Jacob Garrett in 1914, at which point Samuel got out of the milling business and moved to Bair Station with family and took up watchmaking.

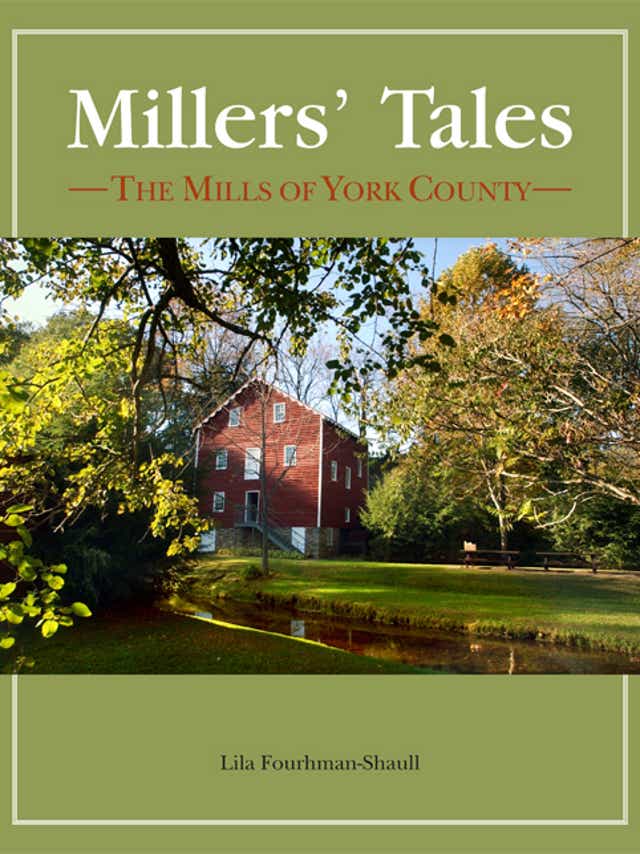

A.L. Menges & Bro. Mill (Hershey) – The third mill that was part of the lawsuit in 1910 was A.L. Menges & Bros. It is one of the oldest mills in York County and located in the small community of Menges Mills, which was named after the mill. The builder of the mill (about 1750) is not certain, but likely someone within the Hershey family, probably Andrew Hershey, Jr. He died in 1750, and the mill eventually went to son Christian Hershey, who sold it to his brother, John, in 1762. The original mill operated as a saw and hemp mill. By 1783, the original mill was torn down and a larger one built, which still stands today. The mill began to process grain for human and animal consumption, which continued into the 1900s.

The mill became the property of John Hershey, Jr. in 1827. By 1830, John’s son-in-law, Peter Menges purchased the property. The mill was owned and operated by the Menges family from 1830 to 1963, at which time it was sold to the Colonial Valley Corp. At the time of the lawsuit, it was owned by Alvin L. Menges (1870 to 1918) and his brother William H. Menges (1872 to 1966). William, also owned a mill at Rt. 116 and Mill Road. This mill was not part of the lawsuit. By 1910, Menges Mills was also using a Fitz water wheel. The company began in Hanover in 1840, by Samuel Fitz (1808 to 1877) followed by his son John Fitz (1847 to 1914).

By 1850 most water wheels had an iron center hub, but the rest was built with wood. By the late 1800s, the company had developed an all-metal water wheel with curvilinear buckets allowing for very high efficiency. Wooden wheels would leak water and were at best 70% efficient, usually much less. The Fitz Water Wheel claimed 90% efficiency. Also, they would not freeze up in winter as easily as wooden wheels. Water turbines ranged from 40% to 95% efficiency. However, waterwheels did very well with low-volume water, which became important to the mills involved in the lawsuit. More on this later. The Fitz Water Wheel Co. went out of business in 1965.

S. Morgan Smith Co.: Stephen Morgan Smith (1839 to 1903) was a Moravian pastor and inventor. After being forced out of the pastorship due to health reasons, he returned to York, where he had pastored the Moravian Church for a time. S. M. Smith invented a powered washing machine and began his business. By 1876, he went on to design and patent a water turbine for the milling industry. These became quite popular because of their durability, and they did not freeze up easily during the wintertime. However, they required greater water volume to operate, a major issue for the mill owners along the West Branch of the Codorus in the early 1900s. S. M. Smith Co. went on to develop turbines for the growing demand for electric. By 1959 the company was purchased by Allis Chalmers. In 1986, it was purchased by VOITH, resulting in several spin off companies: American Hydro (now Weir), Precision Components, and Precision Calibration and Testing Corp.

The following magazine article summarizes the situation and lawsuit. This article also made great advertising for the Fitz Water Wheel Co. Fitz was no doubt an advertiser.

The witness

From the American Miller magazine, May 1, 1912, under this headline: “Pennsylvania Waterpower Case Proves Efficiency of Water Wheel.”

Last March Mr. W. G. Kraft was awarded $2,550 by a jury in York county, Pa., in his suit against the Hanover & McSherrystown Water Company. Mr. Kraft was suing the water company for diverting a “six-inch pipe full” of water from his stream, and the case developed some interesting points, particularly in regard to water wheel efficiency.

Some years ago the water company installed a pumping plant on the west branch of the Codorus creek, some distance above Kraft’s mill. The stream is a small one, and Mr. Kraft had been using steam for some years to help out his waterpower. He always had to use the engine from three to four months in the year. The pumping plant, of course, made conditions worse, but Mr. Kraft then installed the I-X-L Steel Overshot Water Wheel, made by the Fitz Water Wheel Company, of Hanover, Pa. This saved him so much water that he did not have to use his engine at all for two years. In spite of the fact that the creek was smaller than ever before.

Meanwhile the pumping plant had been remodeled and greatly enlarged. It kept on taking more and more water and finally they began to pump water through a six-inch pipe from the stream for ten hours a day. This compelled Kraft to use steam again. Then he sued the water company for damages.

They set up the claim that the creek was so small that it had but little value as a waterpower. Also, that the amount of water they were taking from the stream was too small to have any effect whatever on a water wheel working under Kraft’s eleven foot fall. Finally, they claimed that he hadn’t suffered any damages at all, since he was able to prove that he had to use steam for years previous to the installation of the pumping plant, and yet had been able to run continuously without steam for several years after the plant was in operation.

Mr. Kraft brought a number of witnesses to prove that the increase in power after the pumping plant had been installed was due solely to the fact that he had installed an I-X-L in place of his old waterpower. He proved that while he had always used steam in connection with the old power, he had made such a saving by the installation of the I-X-L that he would have never needed an engine to help it if the water company hadn’t increased their diversion of water from his stream.

The fact that he was able to run without steam after he put in the I-X-L had the effect of proving what the actual value of waterpower was. Judging the value of the waterpower by the work Kraft was able to get out of it by means of his Steel Overshot, the jury decided that, that six-inch stream of water was worth $500 a year to Mr. Kraft and they gave him $2,550 for damages sustained from 1906 to date. This does not cut him out from claiming damages from this time on for continued diversion of water.

Had Mr. Kraft continued to use his turbine and steam engine instead of putting in the I-X-L, he probably would not have gotten any damages at all, or at best a very small amount. The water company would have then been able to show that the waterpower had never been sufficient to run the mill, and also that the six-inch stream they diverted from the creek for ten hours a day would have had very little effect on a turbine under an eleven foot fall. Therefore, the efficiency of the Steel Overshoot Water Wheel entered largely into the case, and the result is quite a victory for the I-X-L as well as for Mr. Kraft.

From Thomas Yingling: Although this article only featured William G. Kraft as the plaintiff, separate lawsuits were filed by Samuel F. Dubs and Alvin L. Menges. With $1,452.88 being awarded to each of them. During the 1906 to 1910 time period, severe droughts during the summer exaggerated the problem. Plus, the Western Maryland Railroad – pumping water for their engines at a watering and coaling station just south of Kraft’s Mill, at Valley Junction from the Sinsheim branch of the Codorus Creek – took away even more water. Although they were not part of the lawsuit. Ironically in 1911, a major rainstorm occurred and wiped out the railroad crossing the Codorus Creek just south of Kraft’s Mill. Waterpower is free power when you had sufficient water.

The questions

Many who live in York County appreciate the rights associated with owning property: privacy, independence, and autonomy to name a few. However, those rights diminish when resources, such as water, transend individual properties, flowing from one boundary line into the next.

The cases in this article showcase the intersection of natural resources, livelihoods, and property rights. More importantly, we witnessed how overstepping boundaries hurt others, resulting in damages beyond repair. How can we, as a community, both respect each others’ rights and livelihoods, while sharing in the natural resources that eclipse individual boundary lines? What can we do to safeguard our own rights while seeing that our actions don’t infringe on others?

Related links and sources: Friends of Codorus Valley Area Historical Society; Map, Thomas Yingling; Kraft Mill photo, York County History Center; top Menges Mill photo, Joe McClure; Other Menges Mill photos, York Daily Record.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: Notable York County history stories, initiatives, 2021-22 - York Town Square

Pingback: Some see foul canal, but Codorus Greenway to turn creek into park

Pingback: A search to know more about York County mills: Witnessing York