Peaceful path has long witnessed conflict

The situation

You could say that no piece of ground in York County has seen more history of import – and at times conflict and battles – than the land within and around Native Lands County Park.

That park occupies a hillside above Lower Windsor Township’s Long Level.

A park brochure lays out a sampling of events that have unfolded in that land along and above the Susquehanna River.

“Although the trail’s path across rolling meadows presents a peaceful scene today, this land has seen much controversy. Battles for possession between the Seneca and Susquehannock, border conflicts between the Penns and Calverts, and modern-day debates about development versus preservation are all part of its history.”

We unpack the Native American story in The Witness section below in the form of a compact timeline. We would say for now that when European settlers started crossing the Susquehanna into future York County to farm, they did not carry a rifle in one arm and clear fields with the other. By then, the Susquehannocks were largely absent from the river’s west bank.

Further, as a general rule, the Penns sought treaties with Native Americans before licensing settlers to move onto former American Indian land. All this meant that early settlers worked fertile, well-watered land, with trade routes to Philadelphia and Baltimore markets, a moderate climate and relationships with non-hostile Native Americans. Future York County farmers and merchants were blessed with resources that would allow them to prosper.

The border conflict indicated in the brochure relates to settlers battling on behalf of Pennsylvania (the Penns) or Maryland (the Calverts) and, really, which colony they would live in.

Here’s a summary of those difficult days – a moment that eventually led to the surveying of the Mason-Dixon Line from 1763 to 1767:

1729-1736: Future York County

Border fight becomes ‘war’

Marylander Stephen Onion secures permission to develop Pleasant Garden located in present-day Long Level. He sells the house and land to fiery fellow Marylander Thomas Cresap in 1731. The presence of Cresap and his attempts to evangelize area settlers to Maryland’s side helps bring on a border conflict.

Marylanders and Pennsylvanians wage what becomes known as “Cresap’s War.” The Penn proprietors become concerned as allegiance to Maryland grows. They fear losing thousands of acres. Arrests and counter-arrests become common.

“Cresap’s War” comes to climax in 1736 when Cresap, accused of murder, was sequestered in his Long Level house, surrounded by armed Pennsylvanians. He is captured after his foes set his house on fire and was transported to prison in Philadelphia. He gains his release after the Calverts and Penns sought to work things out and moved to western Maryland where he again was deeply involved in frontier affairs.

One of the two Susquehannock forts in the Long Level area from about 1665 entered into this land dispute.

Historian June Burk Lloyd writes: “William Penn claimed the land north of the fort and Lord Baltimore the land to the south. Maryland granted patents on land Pennsylvania claimed. By the time the proprietors of those colonies got around to fixing the location of the fort, it was long gone. The case dragged on for nearly 75 years. Although Augustine Herrmann’s map of 1670 shows a Susquehannock fort on the west side of the river near the 40th parallel, probably the Oscar Leibhart site, Pennsylvania’s witnesses were more skillful at confusing the fort with one purportedly located on the east side of the river at Octoraro. The result was the Mason-Dixon Line, surveyed 1763-1767 about 16 miles south of the fort.”

Native Lands County Park itself is part of the brochure reference to the development versus preservation issue. It was part of a settlement in the 21st century that also involved York County’s acquisition of Highpoint, a prime piece of hilltop land towering to the north as you walk around Native Lands park. That acquisition, which involved eminent domain and came at a steep cost in tax dollars, will keep this historic land green and free from housing developments.

Thus, the story of this land – Native Lands County Park – ends well.

“Today this landscape is a place for sharing a common heritage,” the brochure states. “The land’s healing nature was evident when volunteers from the Mason-Dixon Trail System, York Hiking Club, Lancaster-York Native Heritage Advisory Council and the Dritt family worked with York County staff to prepare the site for public use as a park.” The Dritt family were early 1800s owners of a large house, now the restored Zimmerman Center, and a nearby family cemetery.

And now the Native American story, a story that didn’t end as well.

THE WITNESS

Prehistoric times

“At some remote time in the past, perhaps more than twelve thousand years ago, a single human being became the first person to see the Susquehanna River. In all likelihood he approached the main stem of the river from the west by following the downstream course of one of its tributaries. He did not call it Susquehanna, nor did he stand in awe of its size and beauty. His people and their ancestors had seen and crossed many rivers of this new land.”

So begins Barry Kent’s “Susquehanna’s Indians” and so begins the story of what will one day become York County. Other American Indian groups would follow, and we’ll provide a glimpse of them. But we’ll spend most of our time to when American Indians meet the Europeans and written history begins.

1200 – 1400: Lower Susquehanna River

Native Americans carve in river rock

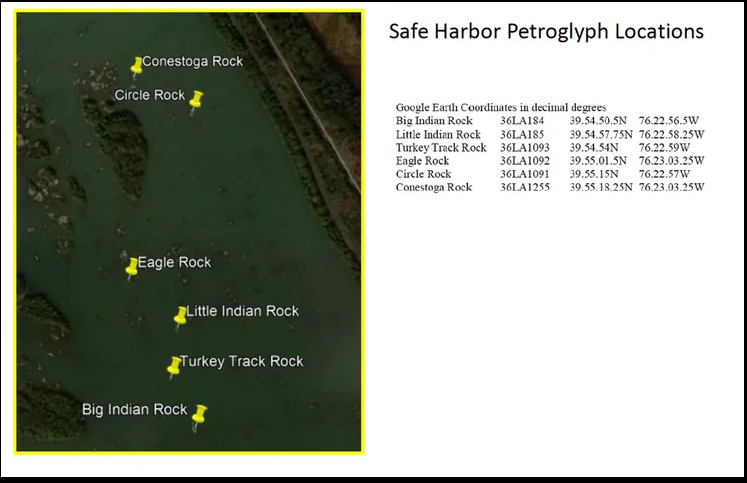

Native people use stone tools in creating images to work the hard schist of rock islands in the Susquehanna. They used a round hammer stone and quartz chisel to create the rock art.

One image, that of a serpent, aligns with the sunrise position of the winter solstice – one of four alignments of snake-like petroglyphs with sunsets or sunrises tied to seasons.

“This part of the river must have been a very special place to have it be chosen to mark such an important day – the birth of a new solar year, year after year,” the Susquehanna National Heritage Area writes about this Safe Harbor area. “It still is a very special place, and still marking each new season.”

1300-1600: Lower Susquehanna River

Shenks Ferry tribe disappears

Shenks Ferry American Indian tribe is small yet widely dispersed throughout the Susquehanna Valley by about 1300. By the mid-1500s, these American Indians converge in stockaded villages in future Lancaster County. Later, the Susquehannock group arrives from points north and kill, drive away or incorporate the Shenks Ferry people.

The Susquehannocks, an Iroquois-speaking people from future New York state, migrate south in the 15th century. They separate from the Iroquois, a federation of the Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca and Onondaga. Some believe that the confederation of states that became the United States – adopted in York as the Articles of Confederation – followed the Iroquois lead.

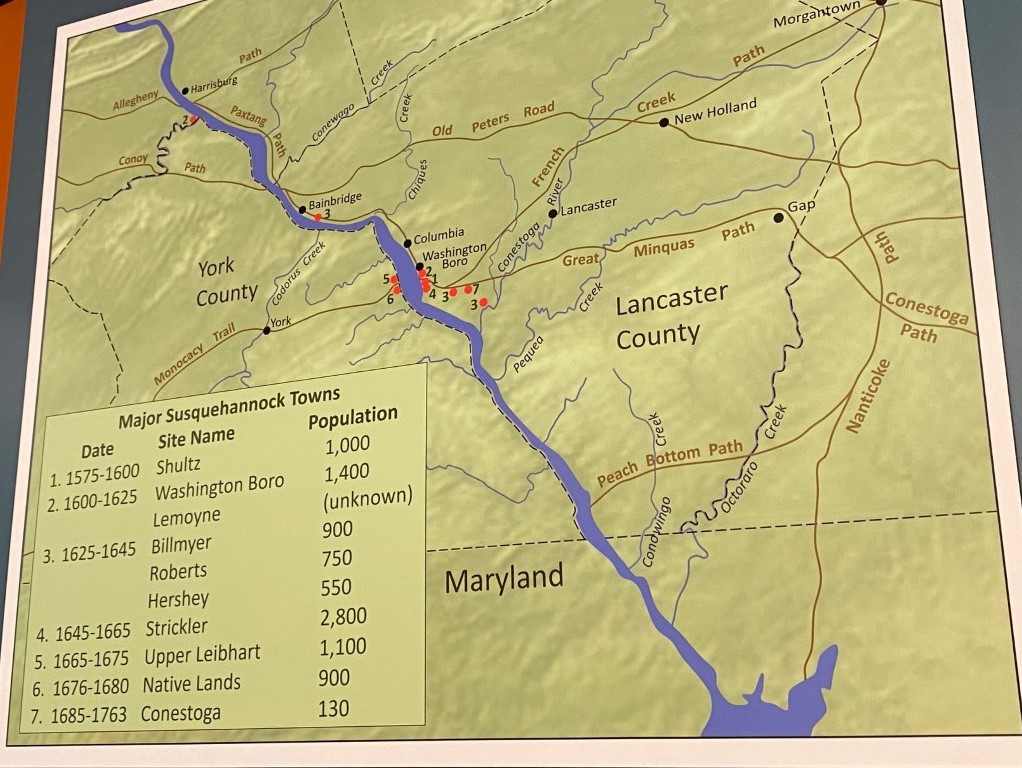

The Susquehannocks seceded from the Union, reached the lower Susquehanna River about 1575 and established a village at the site of present-day Washington Boro in Lancaster County by about 1600. There’s evidence that the Shenk’s Ferry and Susquehannocks overlapped in this region in these early years.

It’s these Native Americans from the village in Washington Boro that would meet with Capt. John Smith in 1608.

1608: Lower Susquehanna River

Tribe named for ‘muddy river’

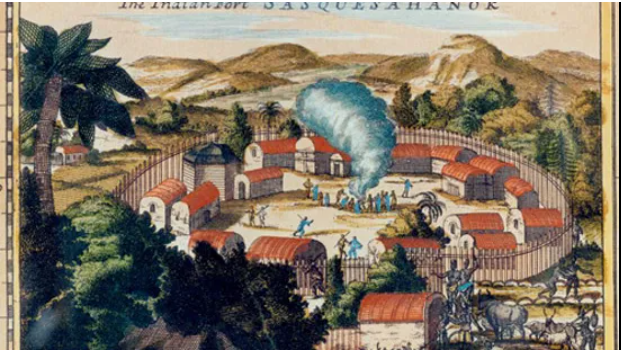

Capt. John Smith and the Susquehannock people meet near today’s Port Deposit, Md. It is Smith who calls the tribe “Susquesahannocks,” an Algonquin word translated to mean “people of the muddy river.” Algonquin was the language spoken by many Nation Americans of the Chesapeake Bay.

In those decades, the Susquehannocks lived in stockaded villages first on the Lancaster side of the Susquehanna and later on two sites above Long Level. They quartered in longhouses, measuring 20 feet by 90 feet, and able to accommodate five often-related families. There’s evidence of 16 longhouses standing in an acre of land. The groups of houses were surrounded by more poles driven closely together into the earth, forming a palisade for protection from enemies and wild animals.

The Susquehannock society was matriarchal, meaning these American Indians trace their descent through their mother, and married men live with their wives’ families. The Susquehannock people have been compared in culture and in language with New York’s Iroquois. If the Iroquois were any indication, their religious practices involved hope and thanksgiving and fear and mourning.

The Susquehannocks farmed, raising the “three sisters”: corn, beans and squash. Women were in charge of farming, also contributing by gathering seeds, nuts, insects, reptiles and mollusks. The men talked politics and hunted in the heavily wooded region and fished in the Susquehanna and its tributaries. The Susquehannocks tended to move to new villages about every 20 years.

Occasionally, traders and other Europeans would marry Susquehannock women. Jacob Claesz was one such trader, living with the Susquehannocks about 1648. He later served as an interpreter and peacemaker for the proprietors of Maryland. In 1682, he was prosecuted for, among other things, the illegal act of marrying an American Indian woman.

The Susquehannocks were known as well-organized, military people and able traders. Their lower Susquehanna home put them close to European traders of furs on the Delaware and Chesapeake bays.

John Smith is best known as the founder of the Jamestown settlement in future Virginia and his friendship with Pocahontas, daughter of Indian chief Powhatan.

According to Smith, Pocahontas stopped Powhatan from executing him.

1665-1680 – Lower Susquehanna River

Indians form alliance

The Iroquois defeat the Susquehannocks, weakened by epidemics contracted from the Europeans and alcohol.

The two groups have an ongoing battle over control of the fur trade with white traders. The trade is important to American Indians and settlers.

The furs bring great value to Europe, and the Indians become increasingly dependent on European goods, including guns to harvest beavers and other fur-bearing animals.

At about this time, the Susquehannocks are gathered in two villages west of the Susquehanna, their villages lasting about 25 years when resources became exhausted. Those two villages are known today as the Oscar Leibhart (a village of perhaps 1,200 Susquehannocks) and Byrd Leibhart (about 900 people) sites. They are named after farmers who later worked the land.

The preserved sites are located on a hill above present-day Long Level in Lower Windsor Township, the Byrd Leibhart site covered by Native Lands County Park.

The Native Land site, with about a dozen longhouses, was the last site stockaded settlement in the Lower Susquehanna.

By this time, the households of the Susquehannock people were filled with goods from trade with Europeans: copper kettles, flintlock gun parts, iron tomahawks, glass beads and other trinkets.

Later, remaining Susquehannocks join with Seneca Indians and other groups and increasingly become known as the Conestogas. There’s research suggesting that the English coined the named Susquehannocks; the Swedes, trading mostly in Delaware, the Minquas; and the French and Susquehannock enemies, Andastes or Ganatogues, perhaps the source of Conestoga.

“The people who, during the seventeenth century, became known as the Susquehannocks are historically the most important Indians of the Susquehanna River valley,” Barry Kent wrote.

1681: London

Penn gains land grant

William Penn, a Quaker, acquires land via a grant from King Charles II – Britain’s king owed money to Penn’s deceased father

This started what is referred to as “the long peace,” among Native American tribes and the Penn family.

Early on, Penn and his proprietor sons establish a policy of paying American Indians for land before licensing pioneers to settle on it. This practice helps provide relative peace with the Native Americans until the years leading up to the French and Indian War – years that covered the period of York County’s early settlement.

These policies helped Pennsylvania and the Susquehanna region in these early years to avoid frontier warfare between Native Americans, settlers and Pennsylvania’s authorities.

1696: Philadelphia

Penn buys land near Susquehanna

Col. Thomas Dongan, agent for William Penn, purchases the land on both sides of the Susquehanna River from the Iroquois.

Some Conestoga or Susquehannocks refuse to accept this treaty, believing that their long-time foes have no right to the land.

Early on, Penn and his proprietor sons establish a policy of paying American Indians for land before licensing pioneers to settle on it. This practice helps provide relative peace with the Native Americans until the years leading up to the French and Indian War.

1733: Future York County

Licenses issued for 74,000 acres

Samuel Blunston, a Lancaster County magistrate and surveyor, issues legal licenses to settlers seeking land west of the Susquehanna River.

The licenses are not final because the land title is not resolved with the American Indians.

Blunston issued about 280 licenses for about 74,000 acres in the future York County.

1736: Philadelphia

Penns buy more land

The Penns purchase land west of the Susquehanna in a treaty that was acceptable to American Indians, who continued to dispute prior agreements.

Even after William Penn’s death, his heirs follow the policy of not authorizing settlements without first making treaties with the Indians.

Pennsylvania authorities made about 30 land purchases by treaty between 1682 and 1793. The Penns now owned “all the river Susquehanna, and all the lands lying on the west side of the said river to the setting of the sun. … .”

1748: York County

Native Americans live in the hills

The family of Jerry Dietz of Seneca and German ancestry settles in York County.

Families that included marriages to Susquehannocks faced legal issues. The Dietz family attempted to live quietly in the hills, avoiding prosecution and maintaining their culture.

In the 1950s, the Dietz family participated in Native American gatherings. Jerry Dietz’s future wife was asked: “You do know that you’re marrying an Indian, don’t you.”

1758: York County

Settlers clash with Indians

The French and Indian War inflames conflicts between settlers and American Indians that had largely escaped the county because of the Penns’ policy to pay Native Americans for land.

During a raid in western York County (now Adams County), American Indians capture the Jemison family. “My dear little Mary,” Jane Jemison tells her daughter after her family’s capture, “I fear that the time has arrived when we must be parted forever. We shall probably be tomahawked here in this lonesome place. …” Her mother urges Mary to remember her native tongue and to say her prayers every night.

The Indians kill her parents and siblings, but spare Mary. Mary later survives two American Indian husbands. Despite chances to return to white settlements, she voluntarily lives among her adopted people. She becomes known as “the White Woman of the Genessee.”

1763: Lancaster

Conestogas targeted

The remaining Susquehannocks in the Lower Susquehanna are part of a peaceful Native American group, the Conestogas.

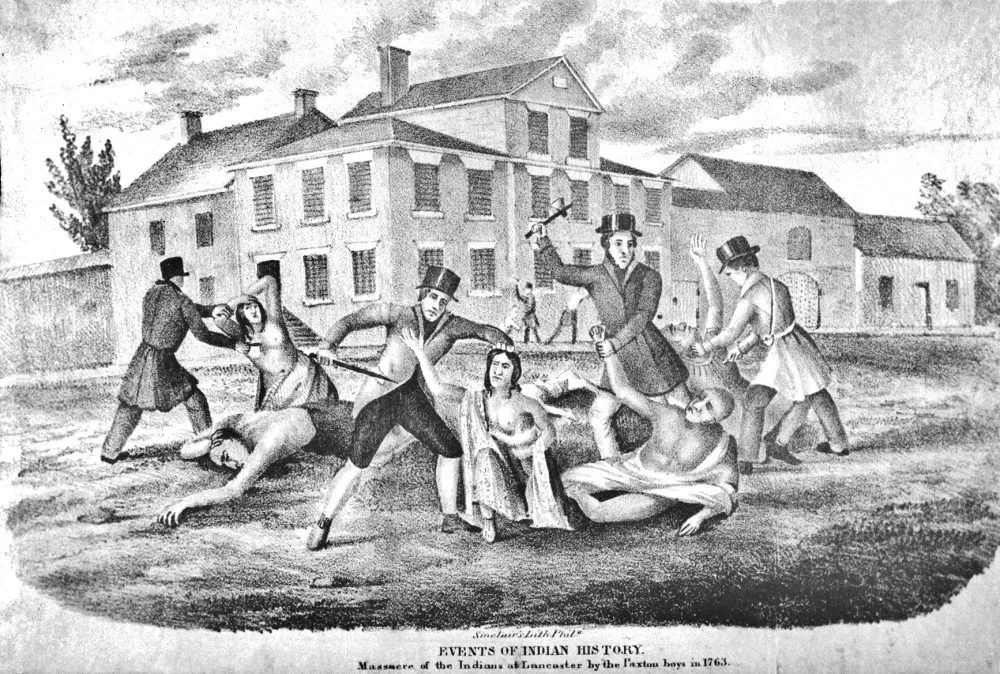

They become targets of violence when a group of white men from Paxtang, near Harrisburg, suspect the Conestogas were somehow involved in an uprising by Native Americans on the western frontier.

Fifty-seven settlers – the Paxton Boys – raid the Conestogas in Lancaster County, killing six.

Authorities detain surviving Native Americans under protective custody in the Lancaster County Jail. The Paxton Boys return, break into the jail and kill 14 Conestogas, including elderly men, women and children.

After the massacre of these Susquehannock descendants, a larger group of vigilantes marched on Philadelphia to fight Native Americans there. Officials met the mob outside of Philadelphia, and the attack was stalled.

The Paxton Boys claimed Conestoga Town in Lancaster County and build two cabins there. Governor John Penn orders them off the land. No Paxton Boys were ever prosecuted.

Two Native Americans, known as Michael and Mary, survive, and Penn presents them with a letter guaranteeing their safety. They live out their days on a Warwick Township, Lancaster County, farm.

Benjamin Franklin later said of the Conestoga attack: “The universal concern of the neighboring white people on hearing of this event, and the lamentations of the younger Indians when they returned and saw the desolation and the butchered, half-burned bodies of their murdered parents and other relations cannot well be expressed.”

After this attack and for decades thereafter, Native Americans lived quietly in the former Susquehannock homeland, living in the shadows as one Native American put it.

Today, more than 3,000 people of Native American heritage live in the land that the Susquehannocks fished, farmed and hunted. The U.S. Census in 2020 counted 1,116 Native Americans living in York County, an 18.5 percent increase over 2010 numbers.

More resources:

- How to make a hand-dug canoe, using a Native American blueprint – PART I – Wandering in York County (yorkblog.com) and Earning Eagle Scout Rank, despite challenges – Part II – Wandering in York County (yorkblog.com)

- Foraging for pawpaws: checking it off my bucket list – Wandering in York County (yorkblog.com)

- Three American Indian tribes, four York County artists – Wandering in York County (yorkblog.com)

- 250 years ago, Paxton Boys massacred remnant of once-mighty Susquehannocks (ydr.com)

- York County Native American Sites Finally Saved – Universal York (yorkblog.com)

- Lancaster’s Darkest Chapter: The Massacre of the Conestoga – Uncharted Lancaster

The questions

When we look across the Lower Windsor landscape, it’s easy to forget its contentious history. It seems like the Native Lands Park was always there, or the Zimmerman Center has simply stood forever. The trees grow in a peaceful resolve overlooking the river as boats pass you by. It’s scene of serenity.

However, as this timeline points out, people have fought over and even killed for this land – and not that long ago. Thankfully, we’re in a time where land disputes can be settled diplomatically. Or are we? Do we still see feuds over estates and property today? If so, why? What can be done to reach a peaceful solution without using violence?

Related links and sources: James McClure’s “Never to be Forgotten”; Susquehanna National Heritage Area, River Roots Blog, “Susquehannock Culture,” “Envisioning the Susquehannock Community”; SNHA exhibit, “The Susquehannock Story,” Zimmerman Center; Uncharted Lancaster. Stephen H. Smith’s Land deed locates the Town of Pleasant Garden. June

Burke Lloyd’s Universal York blog. Horn Farm Center’s series: “The Land and Peoples of the Lower Susquehanna Valley.” Photos, York Daily Record. Timeline of Susquehannock villages, “The Susquehannock Story.”

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: Our courthouses - Indicators of what we like - Witnessing York