the Abandoned African American colony of Yellow Hill

Yellow Hill

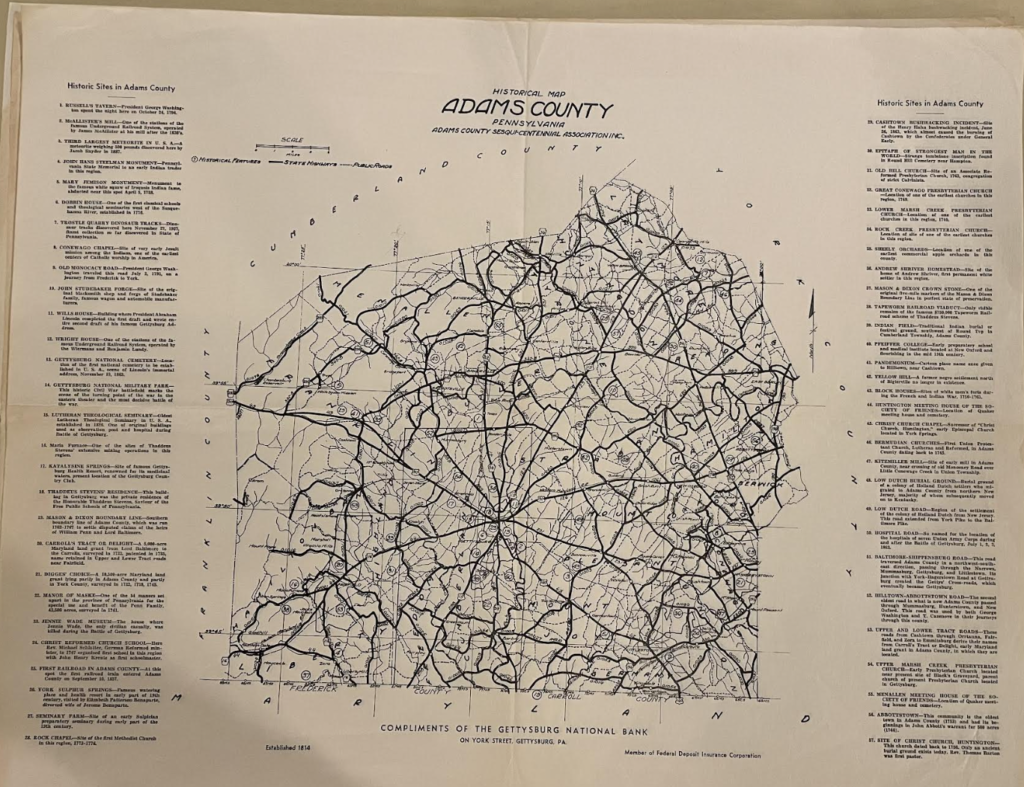

Menallen Township, Adams County

The situation

No one knows exactly what happened to Yellow Hill – an abandoned 19th-century African American colony located in Menallen Township near Biglerville in northern Adams County.

The vault of its history is locked tight. What we do know is that census data puts free Blacks in Butler and Menallen townships in 1800, but local histories claim people settled the area as early as the 1700s. Freedom seekers from Maryland and Virginia brought by the Underground Railroad settled here, too, swelling their numbers to a modest 95 people by 1850.

People escaping bondage could stand on the hill and gaze across the Mason-Dixon Line, a mere 20 miles away, and voice to themselves “I’m free.” A form of self-imposed, collective emancipation. But their exultations had to remain a whisper. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and later 1850 meant kidnappers could cross that symbolic line of freedom to reclaim their bodies back into slavery.

There, on Yellow Hill, they built their shanties by logging the chestnut trees and hand digging their own wells. They found employment as farm hands, laborers, and forgemen for the iron furnaces. Through their hard work, they boosted the agricultural and manufacturing economy in the area. Together, their segregated sanctuary prospered.

Even during the bloody skirmish in Gettysburg during the Civil War, this humble community operated as a safe haven. Blacks in great danger who lived near the battlefields escaped to Yellow Hill. If the Confederate soldiers got their hands on them, these freed men and women could find themselves captured and forced into slavery. Again, this small hideaway welcomed the downtrodden and the oppressed.

Despite this colony’s security, it seemed to vanish without a trace — save for the memory of a church with a bell and a white picket fence, so the legend goes. They wanted a place to praise God, so they formed their own congregation, raising the church in 1869.

Prior to their own building, the residents worshiped together with their Quaker neighbors who lived a few miles away. Adam County’s Quaker Valley lies adjacent to Yellow Hill where locals established the Religious Society of Friends in 1780 and later their meeting house in 1838 (still in use today)

The inhabitants of Yellow Hill also buried their own dead. While the church is gone — reportedly three white men deliberately set fire, a race crime of arson in the 1890s — their cemetery remains. Believed to once hold 30 graves, only three stones are still visible. Many were disinterred and moved to Gettysburg.

Why the name? Biracial families led to light-complexions, often referred to as “mulattoes.” Light-skinned Black people could be referenced as “yellow.”

Despite Yellow Hill seeming to have simply disappeared, we know some of their stories including that of the Mathews and the Griests.

The witness

Edward Mathews and his wife, Annie, lived in a two-story log house down a tree-lined line near Yellow Hill (it still stands today). They purchased the 16-acre property, a rare occurrence for a Black family at the time, for $350 in 1842. There, they raised 13 children.

The Mathews – along with Quaker Cyrus Griest and his wife, Mary Ann – assisted freedom seekers along the Underground Railroad. The Quaker settlement dates back to the 1730s, forming The Menallen Friends — another known Underground Railroad location.

Twice a month during the summer, the Mathews would guide freedom seekers to the Griest’s house, stowing them in their springhouse. Mathews would rap on Griest’s bedroom window to notify them of the special guests. On those mornings, Mary Ann always made sure extra breakfast plates made their way to the secret hideaway.

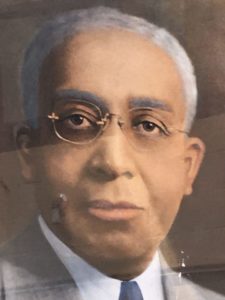

From there, people escaped to York Springs or Pine Grove Furnace where many free Blacks worked. The iconic Iron Master’s Mansion, now a wedding venue, served as another stop. The local hero Basil Biggs also assisted people north from Gettysburg to Yellow Hill. Biggs, a Black leader in the Gettysburg community during the mid-1800s to early 1900s, formed a society to help his African American neighbors called the Sons of Goodwill.

One of the Mathew’s sons, William, ran away at just 14 years old to join the army in 1864. He wanted to fight alongside his older brothers, Samuel (drafted) and Nelson (enlisted). Thankfully, all three survived; however William suffered from a gunshot wound in his right knee for the rest of his life. He was buried at Yellow Hill but later moved to Lincoln Cemetery.

During their time in the U.S. Colored Troops, Black soldiers were treated unequally. They receive lower pay, less food, and lower quality uniforms and equipment when compared to their white counterparts. Their lives, put simply, were expendable.

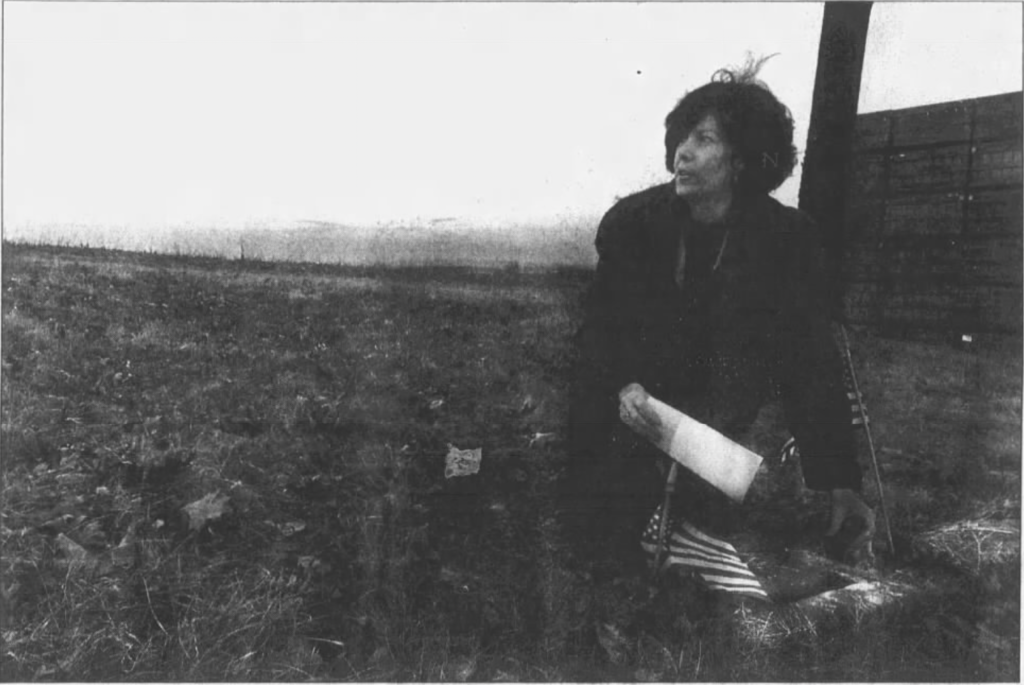

Despite what seems to have been a thriving community, Yellow Hill’s decline remains a mystery. But according to oral histories, many people from Gettysburg remember their sacrifices, trekking up to abandoned colony every Memorial Day to decorate the graves.

One local historian, Debra McCauslin, went as far as to hold a service for the Mathews brothers and other Black Yellow Hill residents who served in the U.S. Colored Troops such as Henry Gooden and Charles Parker, who was wounded during his time with the 3rd Regiment.

Parker was eventually moved to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg in 1936 with no ceremony or service. Maybe they didn’t have time. Or maybe they didn’t care. The answer is lost to history.

The work of local citizens to resurrect curiosity in Black settlements and cemeteries is a form of historical correction. For a long time, African American history was omitted, or even worse, erased, from the canonical record. The growing preservation movement continues in York County with North York’s Lebanon Cemetery and a potter’s field called Penny Heaven.

The work done by preservation groups like this build on the momentum from local research done in the late 20th century. A historiography of the acceleration of Black and Latino history studies can be found HERE.

The residents of Yellow Hill have since disappeared. All that’s left are a few headstones. No one can say for sure when and why they settled there in the first place, but McCauslin theorizes they deliberately chose land next to their Quaker, abolitionist neighbors.

As much as we’re eager to know more of the story, we understand why records are sparse. The Underground Railroad was a dangerous venture. You don’t keep track of things you don’t want others to know about.

The questions

Yellow Hill residents spent their time living peacefully for many decades. Despite this, they abandoned their colony. Today, there’s barely a trace of the inhabitants. Is the average person doomed to be forgotten? Does Yellow Hill even matter? The authors of Witnessing York think so, but what are your thoughts?

The Quakers applied their religious convictions to help real people – those who lived at Yellow Hill. Do you still see such strong religious convictions today?

Related links and sources Black Settlement on Yellow Hill; Segregated in death: Lebanon Cemetery; Top photo, York County History Center. Middle and bottom photo, York Daily Record.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: 'Realizing I was white' at 12: Blacks, Latinos learn much earlier - Wandering in York County