The Green Book: Struggling to find a place to stay while on family vacation

Before integration, Black travelers found respite in certain York County hotels and inns

Yorktowne Hotel, 48 E. Market St. and The Reeves Family, 525 S. Cleveland Ave.

The situation

During the Jim Crow era of segregation in the North and South, Black families experienced trouble finding places to stay while traveling. Hotels, department stores, drugstores, night clubs, gas stations, inns, restaurants, and trailers refused service, simply because of the color of their skin.

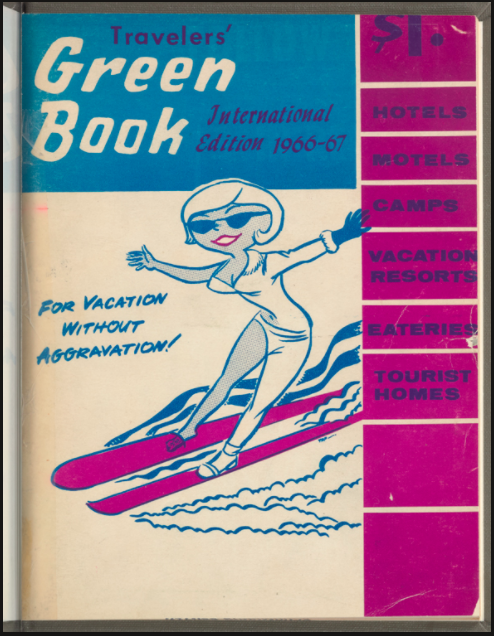

Candacy Taylor, in her book Overground Railroad, looks at the Green Book, a listing of places across the country that welcomed Black travelers. “The businesses listed in it were critical sources of refuge along lonely stretches of America’s perilously empty roads,” Taylor writes about these days of legalized segregation.

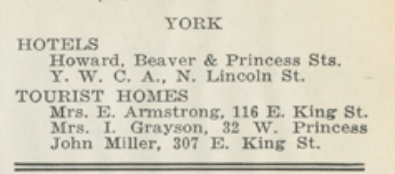

Were there any York County locations mentioned? At least six hotels and inns were deemed safe for Black travelers. These include the Yorktowne Hotel, the Hotel Howard located between Beaver and Princess streets, and the YWCA.

By 1962, the Green Book listed only the Yorktowne Hotel and Mrs. Grayson’s Tourist Home.

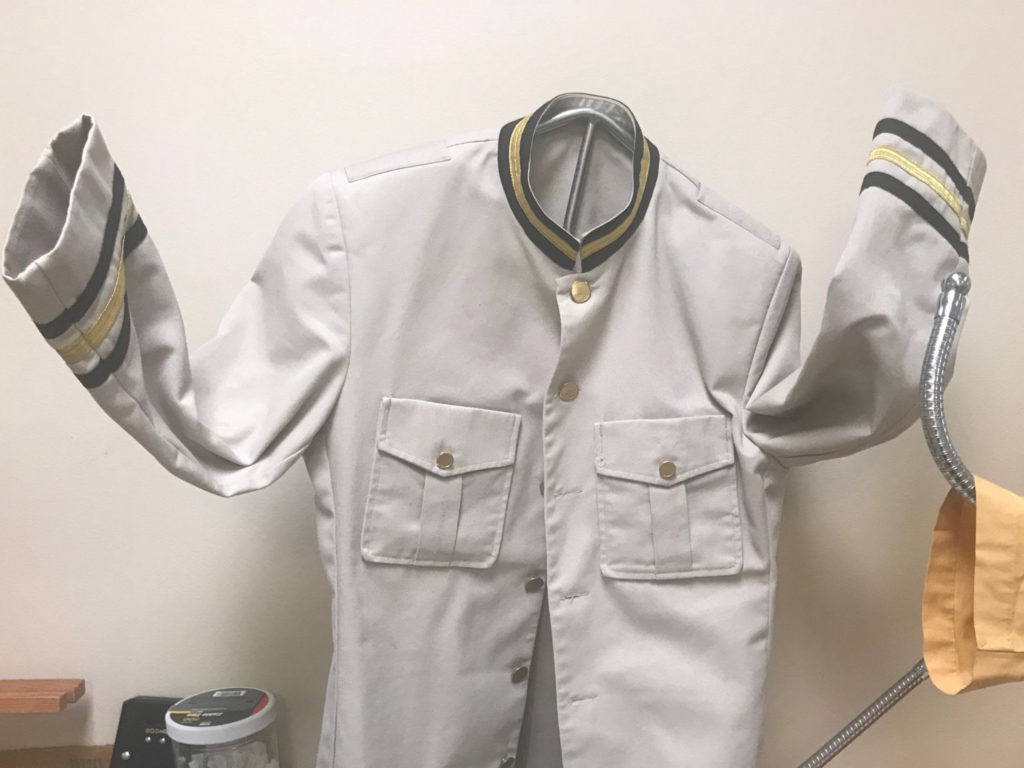

The Smithsonian’s “The Negro Motorist Green Book” traveling exhibit showcases the Yorktowne, which was listed from 1957 to 1964. The three-year tour started in Memphis this fall — its closest site to York County. Artifacts include a wooden host/hostess podium stand, a housekeeping smock and a bellhop jacket.

Taylor believes the bellhop uniform reveals that places in the Green Book weren’t just safe places for Black travelers but also provided jobs. “This uniform represents the labor force behind these businesses and celebrates the employees who humanized these spaces,” Taylor wrote.

However, segregated workers’ bathrooms in the Yorktowne meant segregation just as much as the bellhop jacket symbols inclusion. Further, the late York community leader Voni B.Grimes, a Black man, would tell about how Black Yorktowne employees urged him to seek employment elsewhere. Blacks could only rise to certain employment levels there.

Late in life, Grimes and his wife, Lorrayne, lived in the Yorktowne. He explained that when growing up in York, he knew that Blacks could not stay there so he made it a lifelong goal to do just that.

Inclusion in the Green Book indicates change for the better at the Yorktowne and its city. Another moment strengthens this theme.

In the late 1980s, the Yorktowne barred the Ku Klux Klan, registered as the fictitious Python’s Den, from meeting there. The KKK, in turn, picketed the Yorktowne and unsuccessfully fought its exclusion with the city Human Relations Commission.

The KKK argued that the NAACP had met there so it was discriminatory to exclude the Klan’s all-white membership. As it turns out, the NAACP had white members, and the KKK was legally turned away.

The Yorktowne had completed its turn. It had come full circle.

The witness

How did Black travelers navigate a racist world before the Green Book?

The Friends of Lebanon Cemetery, a restoration and research group, has found two-word newspaper listings of personal accommodations. Locals used word of mouth to locate people willing to host travelers. This meant average Yorkers opened their homes to strangers.

Samantha Dorm of the Friends recognized how people, through friendships and communication, prompted an active network where outsiders could find safe lodgings. She even remembers her mom, Mable Dorm, hosting musicians after concerts.

The Black Devil Band’s visit to York illustrates such a moment.

Band members from an all-Black 350th Field Artillery unit, The Black Devil Band, were turned down from hotel after hotel when they visited York in 1919. White proprietors didn’t want African Americans staying at their accommodations. Luckily, owners of the Belvidere Restaurant, Samuel Armstrong and Dr. George W. Bowles, found them places to stay. One was the home of Helen Peaco.

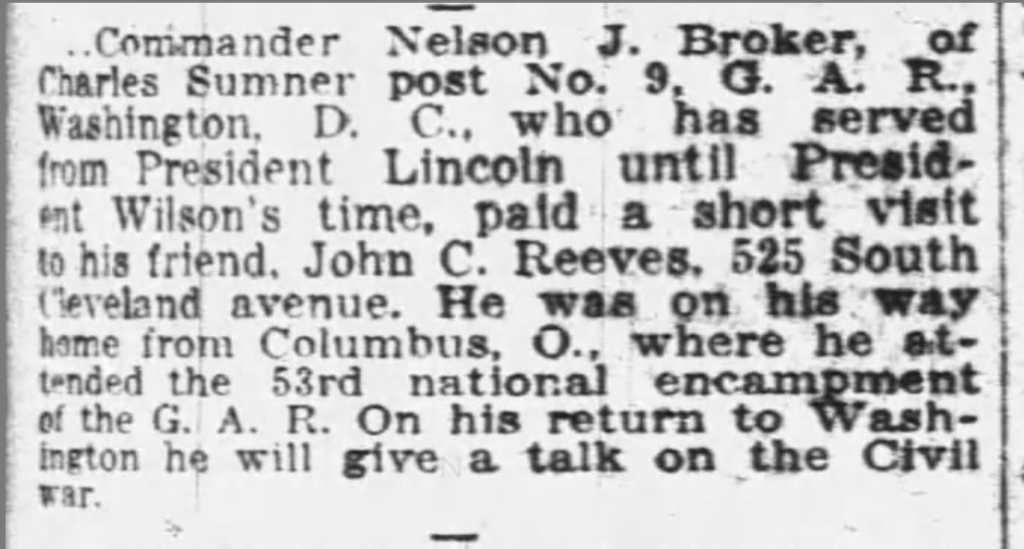

Another such host in these visits was John C. Reeves, who owned a home at 525 S. Cleveland Ave. The Reeves family frequently allowed people to stay, including missionaries just passing through. Commander Nelson J. Broker, who served under President Lincoln, stayed there in 1919. One of Reeves’ daughters, Helen Reeves Thackston, a leader in the community, assisted these Black travelers.

Facing a world of barriers and exclusion, Black Yorkers helped others find safety. This level of grass-roots self-sufficiency shows optimism and perseverance.

The question

The Green Book listed over 9,500 of 70,000 Black-owned, small businesses in the 1930s. That means 86.5 percent of these businesses weren’t mentioned. The Friends of Lebanon Cemetery research shows us the network of resistance through self-help. In what ways can we continue to show support through our networks?

Related links and sources: “Yorktowne Hotel made the Green Book: Black travelers headed to these York County places” by Jamie Kinsley; Overground Railroad by Candacy Taylor; research by Friends of Lebanon Cemetery. Top photo from Ophelia Chambliss. Bellhop jacket photo from York County Economic Alliance.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE