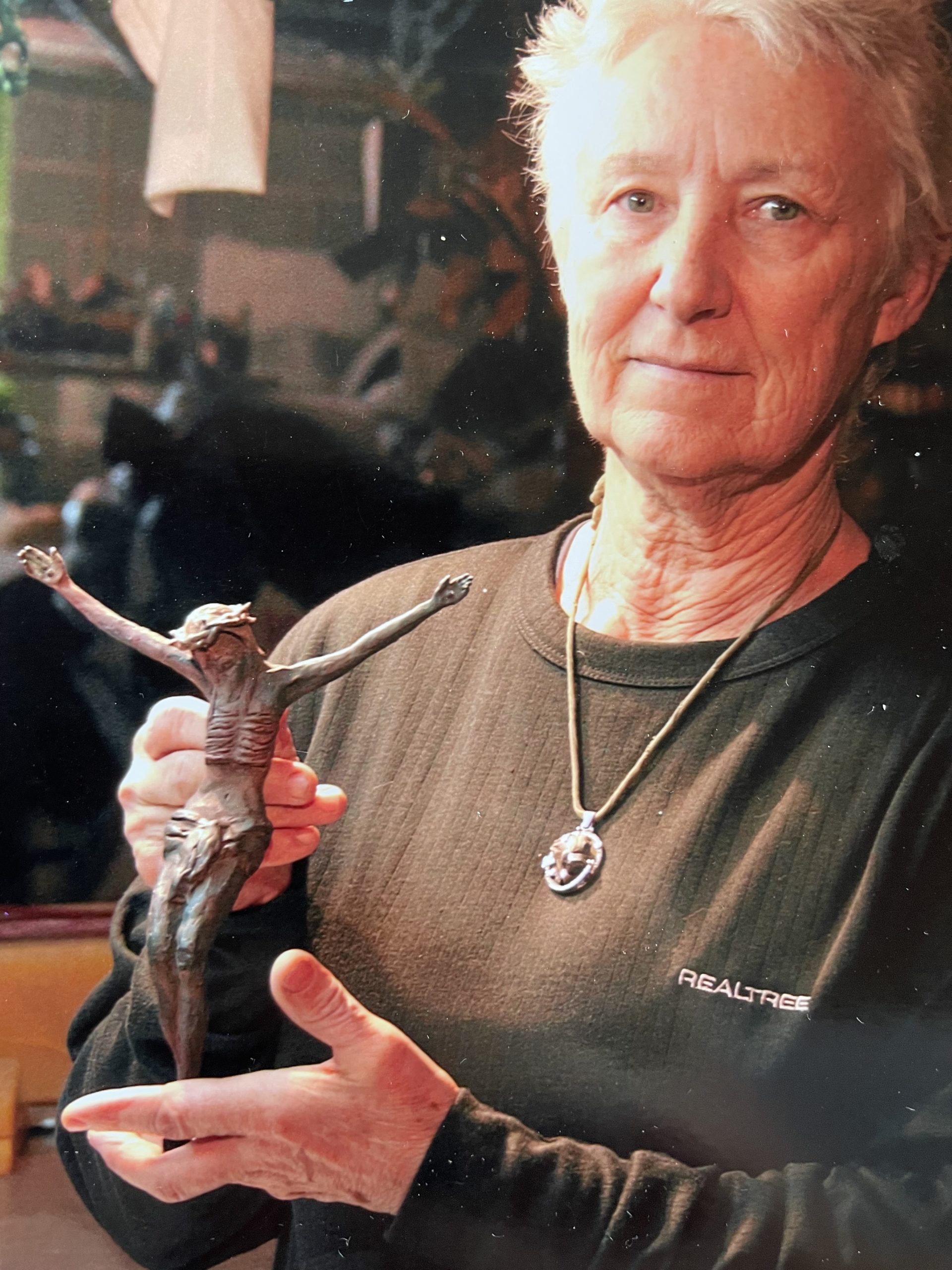

born a stick figure, who is behind ‘the tinker’s’ eyes?

The influential artwork of Lorann Jacobs

Corner of West Philadelphia and North George streets, York

The situation

Empty eyes gaze down toward the corner of West Philadelphia and North George streets in York.

Actually, they’re anything but empty – they’re “tinking.”

A cross between the tin man from the Wizard of Oz and “The Thinker,” the bronze sculpture called “The Tinker” represents York County’s rich industrial history. We are a community filled with makers, builders, and, of course, thinkers. We’re deft in crafting with our hands and minds.

Where did the inspiration for ‘The Tinker” sculpture come from? Lorann Jacobs, the artist, sits down at her kitchen table with a pad and pencil. “Oh my God, I can’t do this,” she thinks. Then, her mind wonders to “The Thinker’s” Auguste Rodin, whose depiction of human form includes pits in the surface.

“I love his work because it’s not perfect, and everything is gorgeous,” Jacobs reflects. She mirrored “The Tinker’s” face and hands after this perfect imperfection. Where did Rodin get his inspiration? His lover and assistant, Camille Claudel.

When Claudel and Rodin sculpted art in the mid-19th century, women simply weren’t respected as artists. Strict gender roles and moral prejudices prevented Claudel from proper training in a male-dominated industry. “At that time,” Jacobs reflects,” a woman wasn’t looked upon as being talented.” It wasn’t until years later that Rodin recognized Claudel’s influence.

Back in her kitchen, Jacobs begins sketching, searching for her own inspiration. “I’m not good at drawing,” she thought. And then she pictured Claudel and all the challenges she faced as a woman.

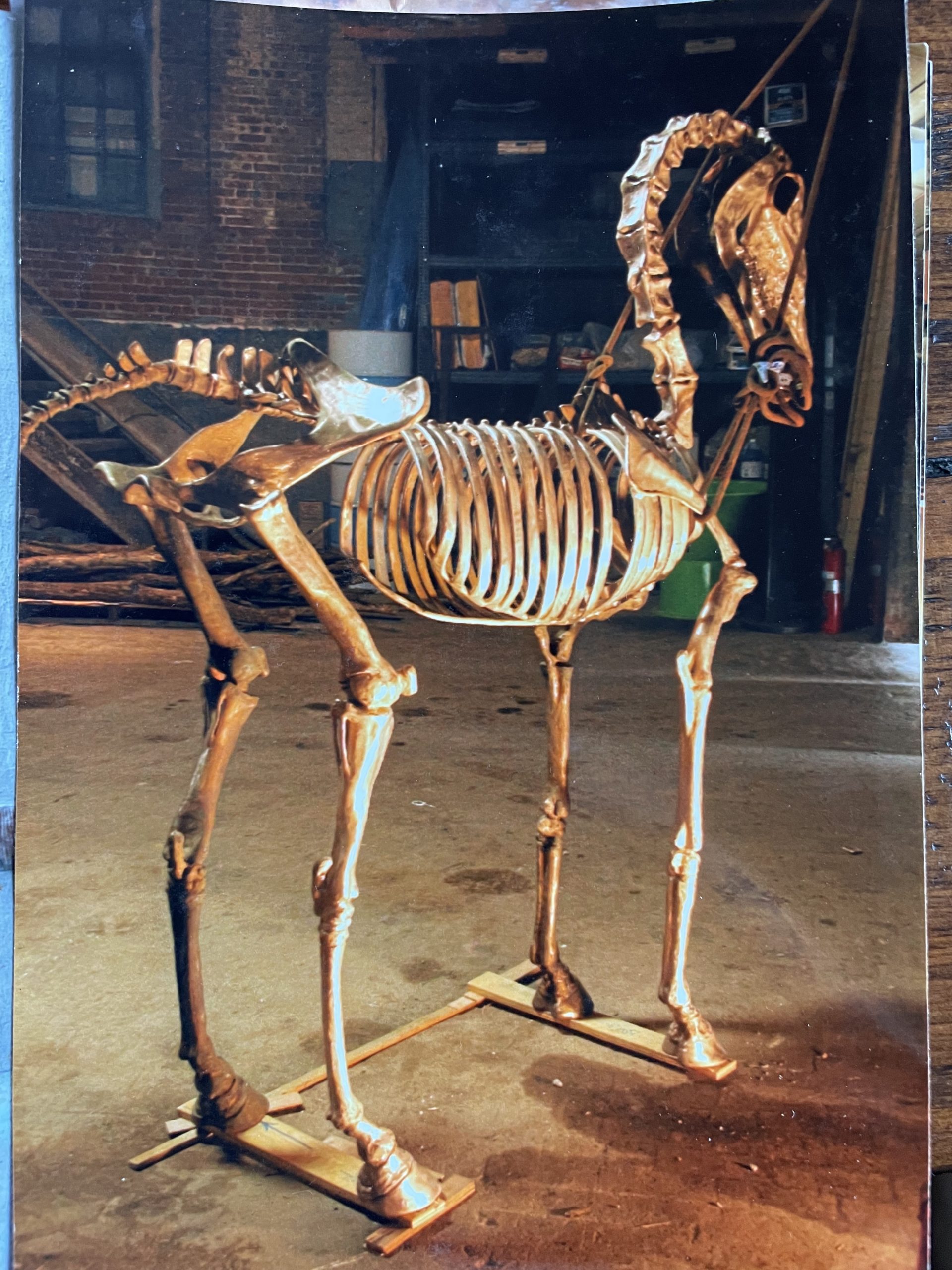

“I thought of the tin man, and then I’m going to put him in the pose of the tinker. It just came.” Her pencil moves across the paper, sketching a simple stick figure. After years of working toward perfect imperfection, “The Tinker,” weighing close to a ton, now contemplates outside the York County Judicial Center. “I always wanted to do a piece for in front of the courthouse,” Jacobs says. “And I never dreamed that would be the piece.”

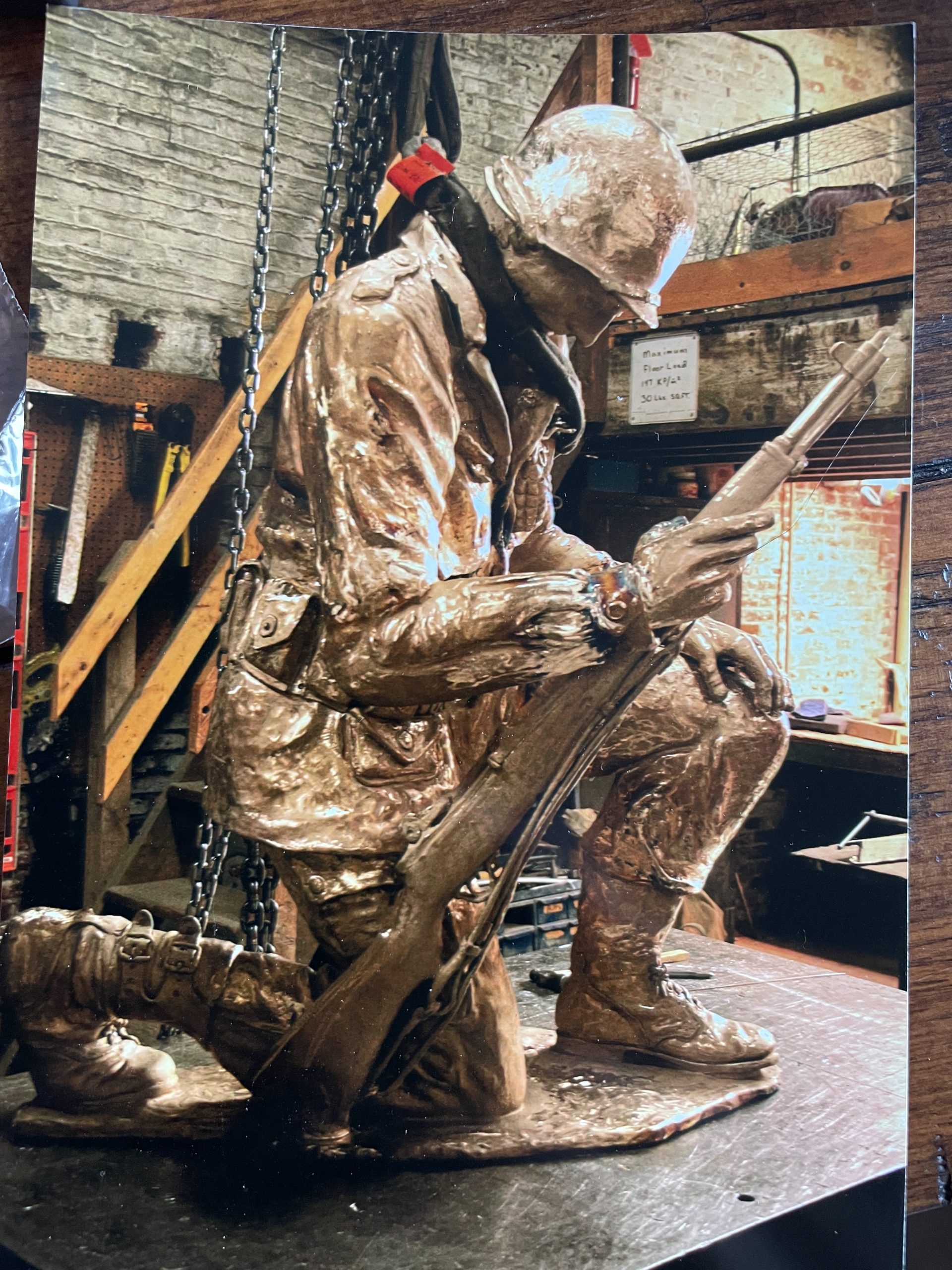

The witness

You may be unfamiliar with her name, but you know Lorann Jacobs’ sculptures: the Vietnam War memorial at the York Expo Center Fairgrounds, Lafayette at the Plough Tavern, Continental Square’s eagle and flag, Brooks Robinson at PeoplesBank Park, war dog Pal along the rail trail, among others. However, breaking into York’s art scene, especially as a woman, was anything but easy.

Jacobs started working with metal at a foundry in Lancaster in the late 1980s. She remembers a few of her male coworkers coughing in her face or calling her derogatory names. Even worse, some would intentionally sabotage her work. As she walked past them carrying a piece of art, they’d push doors open, hitting her and hoping the piece would break on the ground.

We wish we could report that conditions improved as she “proved” herself. They didn’t. After seven years of torment, she left the foundry to pursue art full-time. “It never relented,” Jacobs says. “Once I got out of there, I didn’t have to deal with them anymore.”

When we don’t see people who look like us achieving their dreams, it is akin to having shadows in our own eyes. We need role models to look to for inspiration. It was difficult, but Jacobs finally found a role model in a place unjustly under appreciated for its art – a library.

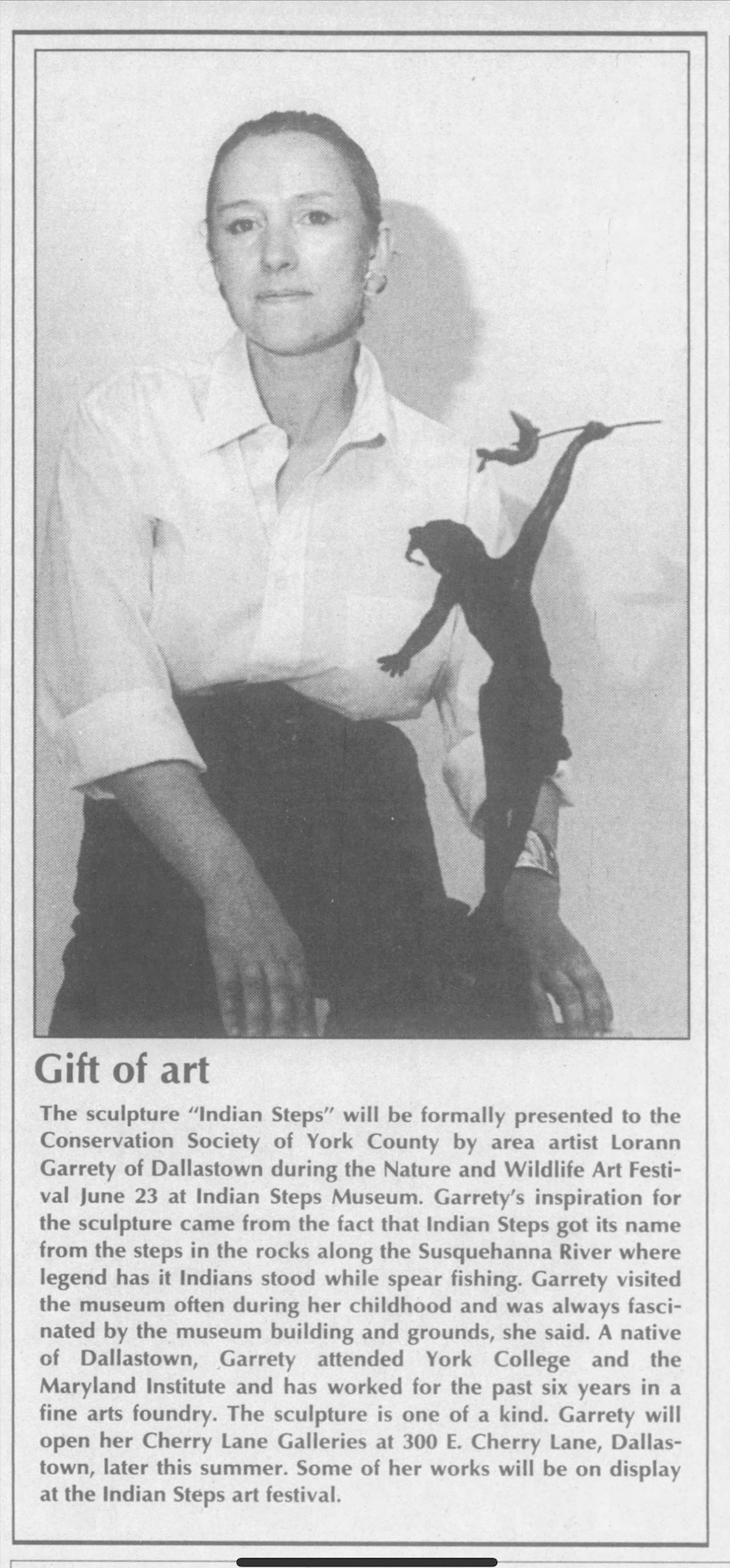

On Martin Library’s campus stands Edith Parson’s Turtle Baby sculpture. “As a kid, I loved that,” Jacobs, a lifelong York County resident says. “I thought that’s the most beautiful thing I [had] ever seen. I never dreamed I could do something like that.” She’d visit the library as a child, gazing up at the magnificent work that stands there today.

Today, a Jacobs’ bronze of a girl stands near the turtle baby – her creation shares space with her inspiration.

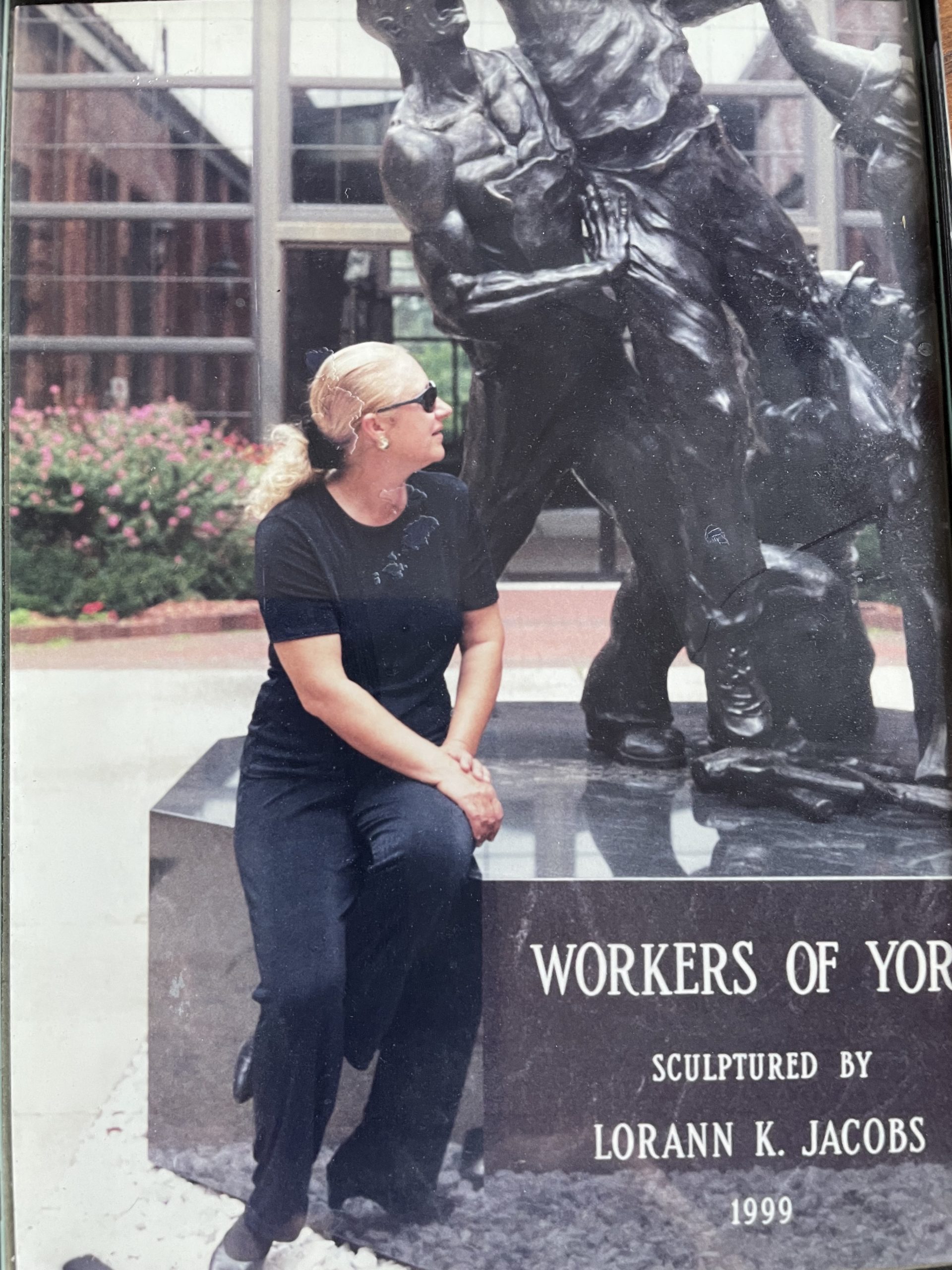

Her break came when she created “The Workers of York” at York County’s History Center’s Agricultural and Industrial Museum as part of York County’s 200th anniversary in 1999. “Didn’t get paid a lot for that, but I did it to prove that I can do it.”

Eventually, she found smaller galleries, and then outdoor shows to sell her art. “It’s hard to find out where to go,” she says. “Other artists wouldn’t tell you. But now you can go to the internet and can find out anything. With Facebook, everyone knows where everyone is going.” Social media is an open source, so sharing is common now.

Without a network of support, “women were just passed over,” Jacobs says. Creating bronze sculptures used to be a space reserved mostly for men. What used to be blocked to women like Jacobs is open to all who can get through the judging panel to make it in an art show. It’s still a competitive field, but with some luck, some support, and a lot of hard work, women can now create and display their bronze sculptures.

In fact, many men help women like Jacobs. Local artist Patrick Sells, for instance, constructed the gear base, lifting The Tinker up for everyone to see.

What began as a crude stick figure on a piece of paper is now a popular public sculpture, rivaling “Lafayette,” for example, as a prop for photographs.

And it was made by a woman.

Jacobs’ influence

Jim McClure’s assessment: Some people today pause and wonder about the heart, mind and hands behind the large bronze public sculptures around York and beyond. Who created these public art pieces that serve as signatures on York’s streetscapes? What was the occasion the making of a sculpture? How much do these monuments weigh? What do they say?

We ask those questions today, and because these statues are made of bronze with its durability, people living 50 years from now likely will wonder about the same things.

How could we make such a prediction? Well, we do so today with the distinct buildings that the York-based Dempwolf firm built. In Harrisburg, architect Charles Howard Lloyd’s buildings command the same curiosity.

So if Dempwolf buildings help define York’s skyline today, might we conclude that Jacobs’ public sculptures will remain a major force in shaping York’s streetscape in 2071?

Further, many of Jacobs’ sculptures were made at the time – the late 1900s to early 2000s – that another largescale art form by women artists in York became very public. Marion Stephenson painted the “Farm to Table” outdoor mural. Justine Landis and Mary L. Straup adapted Lewis Miller’s work to mini-murals in Cherry Lane, also part of the citywide Murals of York program.

Certainly, women were part of York’s art community in the 20th century. The work of Margaret Sarah Lewis, for one, was well known in the community. But public art with size and visibility by women artists in York was rare up until until Jacobs and the muralists set to work. To put a finer point on it, public art pieces by women who sculpted were simply not found in York County before Jacobs’ “Workers of York” was made. So Jacobs can be seen as a key influence in the emergence of the many prominent women artists in York County today.

Lorann Jacobs’ catalog

Generate Embed Code For This List

Hit "Generate & Copy" button to generate embed code. It will be copied to your Clipboard. You can now paste this embed code inside your website's HTML where you want to show the List.

Lorann Jacobs Catalog

· Jacobs has designed and produced an estimated 1,000 sculptures during the last 20 years.

A sample of jacobs’ work can be found at the following locations

- Pennsylvania State Museum’s PA Craft exhibit

- Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church in Camp Hill

- Trinity Lutheran Church in Gettysburg

- Christian Brothers Academy, Lincroft, N.J.

- St. Elizabeth High School, Wilmington, Del.

- Immaculata University Library, Allentown

- Baum School of Art sculpture garden, Allentown

- Boalsburg, Pa.

- Lebanon Valley College

- St. Joseph’s Preparatory School, Philadelphia

- Please Touch Museum, Philadelphia

- Firefighters Park in Rutherford, N.J.

- Private collections of corporations such as Glatfelter Insurance, Liberty Trust, B.F. Goodrich; Rodale Press; AMP, Inc. and Wind Dancer Productions. Her sculptures are also part of private collections in at least 20 states, Japan, Ireland, Germany and the Netherlands.

The questions

Even after years of experience, Jacobs says it’s easy to lose motivation. “I’d noticed that after I finished a big job, I’d get burnt out.” She says, “I could see it. It was like an airplane flying in the air and it stalls. There was nothing you can do about it. It just hits.” Losing creativity happens to others who finish big projects. Jacobs recommends “doing some of the projects that you really want to do for yourself.” Where do you find your muse when you’re lacking motivation?

SPECIAL INSIDER: Jacobs worked for days to create the perfect face for “The Tinker.” Eventually, she turned to a previous project for a clearer vision. Where else in York do you see the “The Tinker’s” face? (Hint: It’s another of Jacobs’ public work in downtown York).

Editor’s note: Jamie Kinsley, Lorann Jacobs’ granddaughter, contributed to this piece. James McClure also contributed and served as editor.

Related links and sources “Dallastown artist Lorann Jacobs reveals how she builds bronze sculptures” by Jamie Kinsley. Top photos by Jamie Kinsley or Lorann Jacobs. Turtle Baby Photo by Martin Library. Bottom photos, York Daily Record

Pingback: Notable York County history stories, initiatives, 2021 - York Town Square