Discovering york-born Arthur Evans and his contributions to the world

Arthur Evans

120 North Harrison Street, York

Matthew Jackson moderates the Facebook group THE VALLEY: People Power and Caring Communities in the Susquehanna Valley. He writes about York-born Arthur Evans’ contributions to the world. Previously, this Hanoverian crafted guest WitnessingYork.com columns about feminist activist Rita Mae Brown, Gettysburg Lincoln Rail Station, Thomas Jefferson’s overnight stay in Hanover and Healing President Lincoln: The curious case of William Henry Johnson (witnessingyork.com)

The situation

Author, philosopher, human rights leader, organizer, activist, humorist and dramatist, York-born Arthur Evans (1942-2011) wore many hats, traveled many miles, achieved much, and enjoyed the banquet of life.

With courage, creativity, good cheer and flair, Evans fought many battles for freedom, human dignity and free inquiry and expression.

After growing up at 120 North Harrison Street, a working-class neighborhood in northeast York, Evans eventually relocated to New York, where he became involved with the Gay Liberation Front and later cofounded the Gay Activists Alliance.

In November 1970, Evans, along with fellow activists Dick Leitsch and Marty Robinson, appeared on The Dick Cavett Show, one of the first times a nationally syndicated television program invited LGBTQ+ rights activists for national dialogue. On that show, Evans came out to the nation, including to his parents back in York.

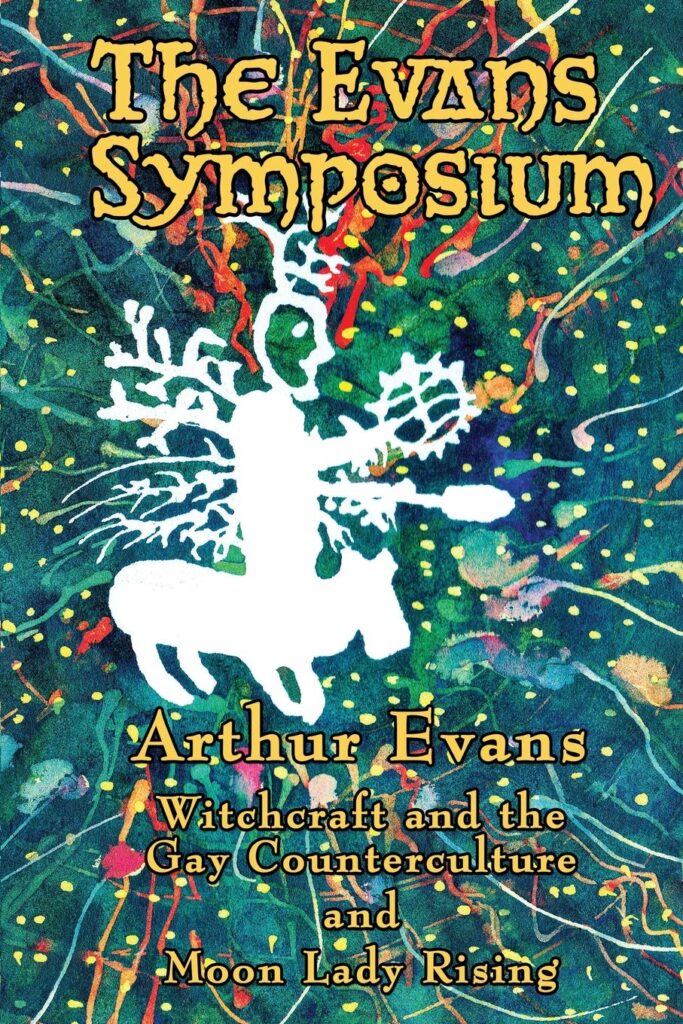

Later, Evans relocated to the West Coast, where he formed the Weird Sisters Partnership commune in Washington state and wrote his widely circulated 1978 book “Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture.”

When he died in 2011, Evans’ obituary appeared in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The San Francisco Bay Guardian, The Irish Times and other prominent publications.

Evans wrote the statement of purpose, as well as much of the constitution of the early gay rights group the Gay Activists Alliance. On Dec. 21, 1969, Evans, Robinson, and several others met to found the Alliance, with a more aggressive ethos than the Gay Liberation Front. It had 12 starting members.

A serious student of philosophy who studied at Brown University and in the doctoral program in philosophy at Columbia University, Evans authored the following: “Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture,” 1978; “The God of Ecstasy,” 1988; “Critique of Patriarchal Reason,” 1997; and “The Evans Symposium: Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture and Moon Lady Rising,” 2018.

More: Arthur Evans, 68, Leader in Gay Rights Fight, Is Dead – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

The witness

Even though I’ve lived here most of my life and strive to be a lifelong learner of history, I didn’t know of Evans until 2023.

Not one whisper, although, from a tip from writer Marc Charisse, I did find this solid York Dispatch article by Greg Gross from 2011.

That’s true with a lot of human and civil rights histories, and the histories of creatives, pacifists, freedom-fighters, and peacemaking advocates and activists. Periodically, there will be a feature article, a modest reference here and there.

But, in our topsy-turvy, information-saturated, short-attention-span society, these references often are drowned out or forgotten or, worse yet, slighted, shaded, or delegitimized.

One could posit a convincing case that, in the Lower Susquehanna Valley of the 20th century, in terms of public history, we’ve limited ourselves to basically a patriarchal, white bread, business-as-usual narrative. By public history, I mean our “community history brand” — the resonating history that shows up as public murals, sculptures, open-to-the-public exhibits, storyboards, and other accessible memory initiatives.

Over the past few decades, much of that is changing for the better, but it’s been a long time and painstakingly coming.

We/I don’t know what we/I don’t read. We/I are/am ignorant of what we/I are kept from. We/I can’t unlearn without knowing what we/I did not know growing up.

We can’t fully evolve in our journey if we don’t see, with unflinching eyes, the hard-earned stations and milestones on the road behind us — the way painstakingly hiked, clawed, and crawled by gritty ancestors, elders and trailblazers.

Hence, the history of York’s one-of-a-kind and most fascinating Black freedom fighter, entrepreneur and Underground Railroad conductor William C. Goodridge (1806-1873) was largely neglected until the last few decades.

It wasn’t until 1987 that a blue-and-gold Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission marker acknowledged the significance of Goodridge and his home at 123 East Philadelphia Street. Thank you to the late York Councilman, Wm. Lee Smallwood, who portrayed Goodridge as a living historian.

It wasn’t until 2016 that the William C. Goodridge Freedom Center and Underground Railroad Museum opened its doors. Bravo to Crispus Attucks and all who made it happen.

Likewise, it may be challenging, but there are responsible ways to publicly tell the history of the uprisings or civil rights unrest of 1968 and 1969. That is true of the York Charrette of 1970, likely York County’s most consequential, people-powered human rights workshop, with sustained results felt powerfully to this day.

More than 50 years after, there is still not an outdoor history storyboard at South Duke Street’s Bond Sanitary Products building – today, The Bond event space – where those historic “civic therapy sessions” were held. Such a storyboard would tell that vital social story that shaped history.

And, how many know that upwards to 100 abolitionists, station masters and conductors who helped likely more than 1,000 enslaved people – perhaps many more – escaped to freedom in York County?

Further, how many know that York’s very square was the home to the daring escape of the brilliant Osborne Perry Anderson, first lieutenant of John Brown and lone surviving Black accomplice in Brown’s 1859 raid at Harper’s Ferry, the tinderbox event helped catalyze the Civil War?

Evading federal surveillance, Anderson hid for days in a hideaway under the stairs in Centre Hall, Mr. Goodridge’s four and 1/2 story skyscraper, before fleeing via a Goodridge rail car to Philadelphia then Canada.

And, does our public history embrace the progressive civil rights, anti-war firebrand Jess (J.W.) Gitt, owner, for 55 years (1915-1970), of The Gazette and Daily in York, a nationally influential newspaper?

And, does our public brand history honor the founder of the international African festival, Kwanzaa? The festival’s founder is Maulana Karenga, formerly Ron Everett, a graduate of York’s William Penn Senior High School.

+++

Back to LGBT+ history: Can our public history embrace York County’s Joy Ufema, the first nurse thanatologist (end-of-life care specialist) in the United States?

Can we embrace LGBT+ firebrands, such as Arthur Evans and Hanover-born Rita Mae Brown, the trailblazing author and human rights champion who fell in love with books at Martin Library?

Brown likely crossed paths with Evans in New York City in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In our public histories, our “community history brand” — the history that shows up as public murals, sculptures, open-to-the-public exhibits, storyboards, and other accessible memory initiatives — what is consistently publicly recognized and embraced and what resonates?

May this be a humble plea to make room in our public histories, our “community history brand,” for the others, the outsiders, the freedom fighters and the peacemakers.

Too often, the bold freedom fighters and mold-breakers, the boat-rockers and pot-stirrers, the colorful and the creatives, the moral instigators and muckrakers, the resistance and its insurgents, the merry pranksters and misfits, the angelic warriors and good troublemakers, the poets and visionaries, the dreamers and deep thinkers, the humanists and the peacemakers have been drowned out, shaded, slighted, or cast aside.

It may be this cultural lapse is partly ingrained due to unacknowledged privilege and/or apathy (thus unconscious), and partly intentional (thus conscious).

I acknowledge my own privilege, blind spots and short-sightedness. I don’t know what I have not read. I am ignorant of what I’ve been kept from. I can’t unlearn without knowing what I did not know growing up.

So, it’s regrettable, disturbing, and, to me, tragic that much of York County’s history of the outsiders, the others, and the peacemakers has been like vapor, coming in dapples of mist from whispered talks and the rumor mill.

That must change and is changing.

Consider that, according to the Trevor Foundation, 46% of youth in our nation who identify as LGBT+ have suicidal ideations. Tragically, too, many actualize the ideation.

As a teen, I was one of them; I suffered from suicidal ideations.

Tragically, too many actualize the ideation. I easily could have been one of them.

Each youth needs role models and figures whom they identify with to show them they have inherent dignity, substance and potential to shine.

Sadly, in much of my life, Arthur Evans and Rita Mae Brown may as well have been ghosts.

Why were they hidden? What were we — as a community — afraid of discovering? Or were we just insensitive and obtuse? All of the above?

A more important question today is, what, with goodwill for all and digital tools at our fingertips, can we do now to redeem or right-size the public, historical brand?

Evans was a serious public intellectual and influential leader who, like York County’s own Rita Mae Brown, a prolific author of over 60 books, was a pivotal figure in the early gay rights movement.

If we are committed to telling a holistic, inclusive history, especially the history of public intellectuals, creatives and human rights trailblazers, York’s public history brand must remember, reckon with, and honor Evans and Brown.

After all, memory is culture.

Culture guides our telling of history.

How we do history nudges culture.

Each speaks to or cross-pollinates the others and vice versa. And they go round and round continuously.

So let’s publicly tell thousands of authentic tales singing and dancing in all directions so they enlighten and empower all walks of life.

Let’s make our public history, our community history brand, so brave and inclusive that it is recognized from miles away as breath-taking, empowering and inspiring to all.

If you or you know someone who is struggling with suicide ideation, please visit the National Alliance on Mental Health for help.

More: J.W. Gitt – Goodbye, Mr. Gitt.

More: Rita Mae Brown: Pennsylvania Roots of Trailblazing Lesbian Activist Rita Mae Brown – Philadelphia Gay News (epgn.com)

The Question

In this article, Matthew Jackson poses a lot of questions. Please take a second to ponder this one: In our public histories, our “community history brand” — the history that shows up as public murals, sculptures, open-to-the-public exhibits, storyboards, and other accessible memory initiatives — what is consistently publicly recognized and embraced and what resonates? In what ways is it an obligation to tell, and re-tell, these stories so our public history is more inclusive?

Related links and sources: Arthur Evans obituary, New York Times and Gay pioneer Arthur Evans dies :: Bay Area Reporter (ebar.com) Top photos: New York Public Library. Bottom photo of Rita Mae Brown, York Daily Record

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE