Post-American Revolution era ripe for protests

Jacob Bixler had a cow

West Market, Beaver Street intersection, York

The situation

The Revolution was over, but an enemy remained on American soil.

And they didn’t wear red coats.

First, cash-starved, debt-ridden farmers were known to build barricades across York County roads to combat this enemy.

The foe was local tax officials, and those barricades were designed to stave off foreclosures of property.

Then authorities moved property auctions to York to avoid such resistance.

The matter came to a head in the county in December 1786 when Jacob Bixler lost his cow to foreclosure after refusing to pay an excise tax. Something like 100 to 200 farmers revolted against such acts, marching into York to reclaim the animal. According to one account, they were ready to make “rough music.” They beat their plowshares into guns and their pruning hooks into clubs.

The people of York met these rioting farmers with guns and clubs of their own, plus pistols and swords. The battleground? Where Market and Beaver streets meet in York.

Henry Miller, veteran of the American Revolution and future burgess of York, struck at one of the rioters named Hoake, who defensively jumped over a wagon tongue. Miller’s sword sank into the tongue about an inch.

After some “boxing and striking,” the crowd dispersed. Some of the rioters were arrested and fined.

“It was, in fact, a cow-insurrection; it brought Manchester and York into a fond and loving union,” W.C. Carter and Adam Glossbrenner wrote in 1834.

The historians did not say whether Jacob Bixler got his cow back, but it seems unlikely.

+++

The American Revolution had ended with treaties in Paris in 1783, and a new era had dawned. It was called the Early Republic period in this region called the Atlantic World. As the Jacob Bixler story shows, the revolutionary spirit was still alive and anything smacking of strong central government raised suspicions in York County and beyond.

And “beyond” meant as far away as Massachusetts where a group of former Revolutionary War soldiers – now farmers facing debt – sounded a similar alarm against state government’s increased efforts to collect taxes.

The federal government’s inability under the Articles of Confederation, adopted in York in 1777, to address this uprising led to the demise of that original American constitution and the rise of the U.S. Constitution.

Even under the U.S. Constitution, protests against taxation continued.

For example, here’s what York College professors Carl E. Hatch and Dean Mellander had to say about the whiskey tax of the 1790s – a tax that was “more than just a tax.”

“It symbolized a policy on the part of the Federalists to make the power of the central government felt throughout the new nation. Other Federalist policies followed, like the Alien and Sedition Acts, with much the same intent behind them, with the result that by 1800 Yorkers were irked with the Federalists whose accent on a strong central government began to look suspiciously like the very thing they fought against in the American Revolution – King George III’s tyrannical government.”

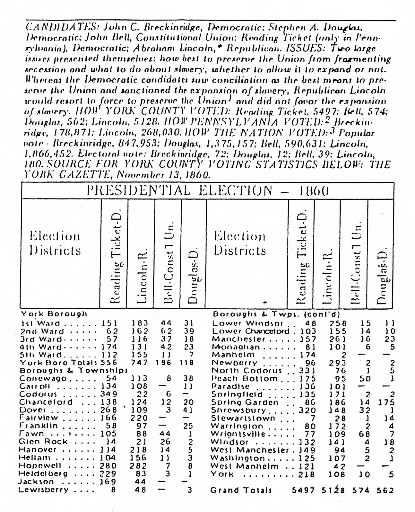

So York County residents protested at the polls, changing their votes from a Federalist majority in early presidential elections to heavily anti-Federalist majorities in national chief executive elections for the rest of the 1800s. That protest against Federalists or Republicans took a pause in 1904 when the county went for Republican Theodore Roosevelt and continued again in favor of Democrats until 1920.

These examples from just one county show that from our earliest days, disturbances, riots and rebellions have marked the American way when gears of democracy jam.

And there’s another example from in the Early Republic era.

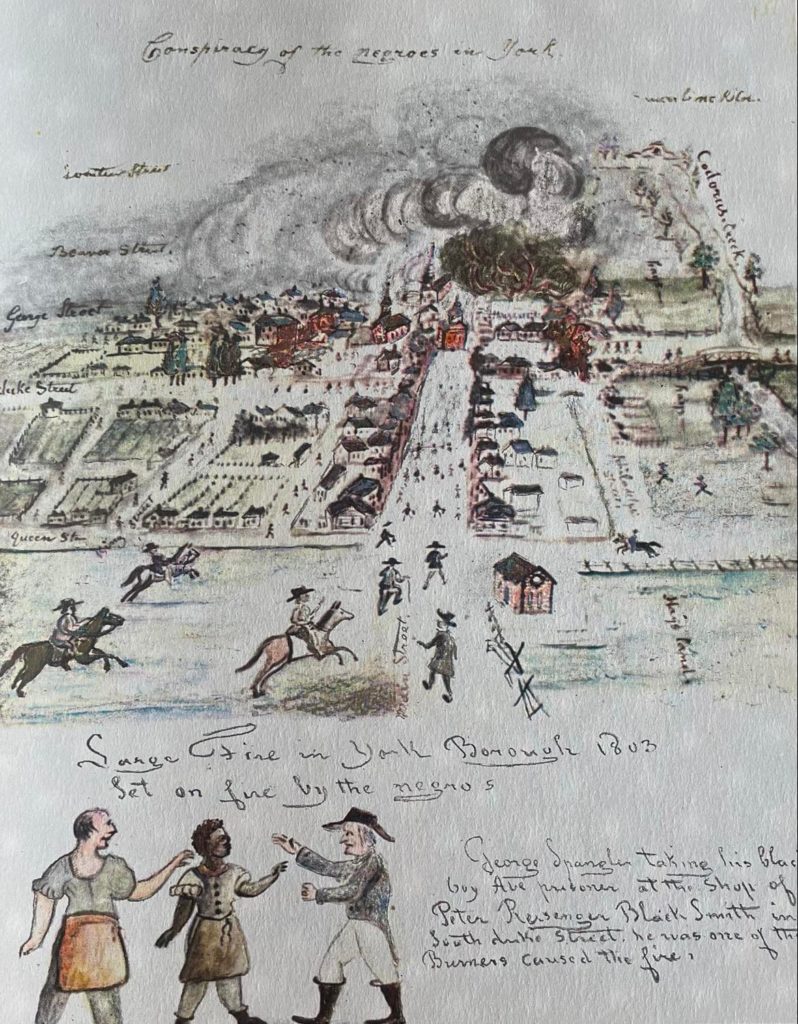

Given the spirit of the age, it should not have surprised York-area residents when the Black population of York rose up in 1803.

But surprised they were.

The Witness

By 1803, York County’s Charles Cunningham had done a lifetime of things in his 17 years.

He was an orphan, a white indentured servant, a soldier and skilled at running away from his adopted hometown of York.

When in town, he was part of a mixed-race group that played pranks and caused trouble.

One older friend stood out: Isaac, a 27-year-old who was enslaved to a shopkeeper in York.

On one of Cunningham’s flights from indentured servitude, Isaac found himself alone and in the worst type of trouble.

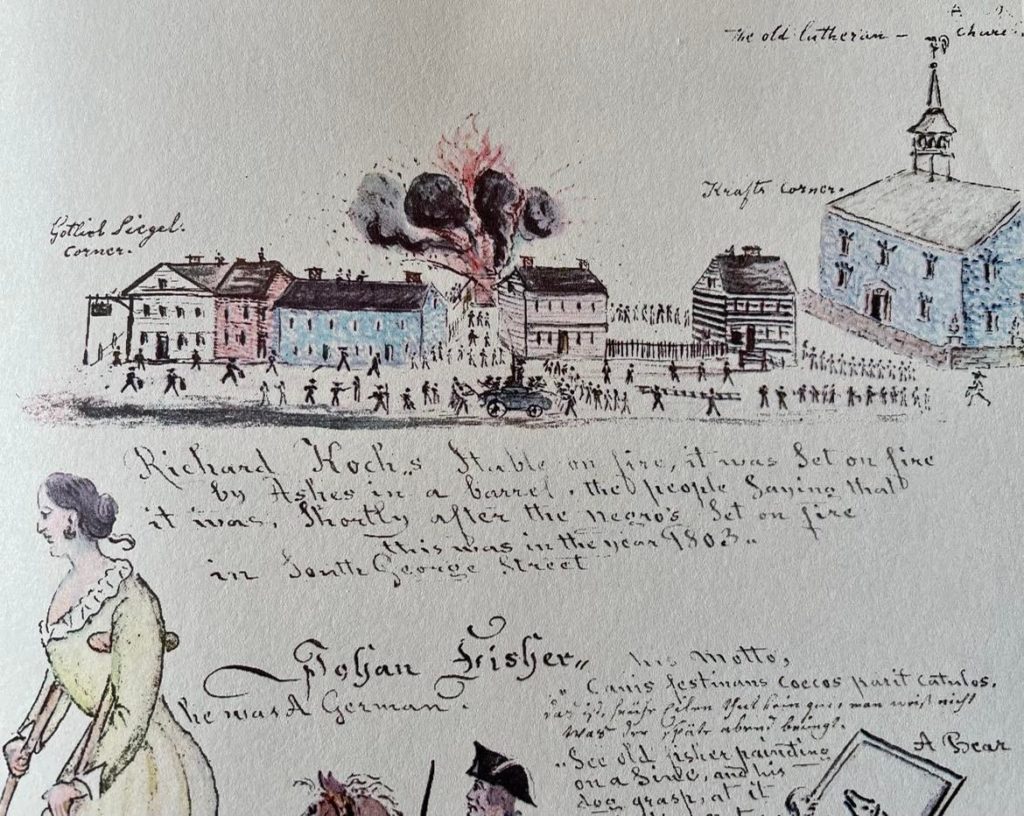

Isaac was part of what is called the Conspiracy of 1803, a series of arsons in York viewed as the first recorded large-scale racial protest against injustice by York County’s considerable free and enslaved Black population.

The friendship of Cunningham, an indentured servant, and Isaac, enslaved because of his race, was bound by their bonds. When they became separated, their lives came to terrifying ends.

For the rest of the story about this protest – a demonstration that did not end well for free and enslaved Black people in the York area – please see: York County’s Conspiracy of 1803: A troubling story (ydr.com). (This piece is based on Dr. Ted Sickler’s dissertation “The Servant’s Lament”.)

The questions

As Jacob Bixler showcased, sometimes voting isn’t enough. Sometimes, democracy isn’t strong enough to act as as a conduit of voices, carrying our opinions and concerns to the policy makers in charge. Sometimes, we must march or find other forms of peaceful protest. What principles do you hold so dear that you would protest? What other forms of communications can we use to let our government officials know how we feel in a peaceful, winsome way?

Related links and sources Ted Sickler’s 2012 doctoral dissertation, University of Delaware: “The Servant’s Lament: Race, Labor, Markets and Rural Reckonings in the Pennsylvania Backcountry of the Early Republic;” James McClure’s “Almost Forgotten;” Carter and Glossbrenner’s “History of York County, From Its Erection to the Present Time,” 1834. Photos, York County History Center.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE